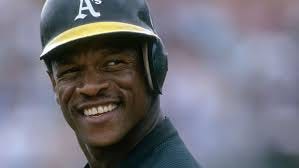

Baseball loses its Master of Time

Whether running, trotting, walking or talking, Rickey Henderson was brilliant at any speed.

He was in a furious hurry to do everything. “Rickey’s taking off!” he’d yell when he took his first steps toward second base. He was also patient and calculating, in historic ways. Nobody took more unintentional walks. Nobody scored more runs, not as long as major league baseball has been played. Maybe there have been better players, and some of his teammates would happily argue there haven’t been. But nobody was more unsafe at every speed than Rickey Henderson was. He was the Man of Steal, but mostly he was the Master of Time, up until Saturday, when he died at age 65.

He kept Cooperstown waiting for the longest time. You can’t get into the Hall of Fame until five years have passed since your last game. When Henderson was 44 he was playing for the Dodgers. He wrapped up that phase in 2003, which meant he was able to sail into the Hall on the first ballot in 2009. But when no other major league club called, Henderson played for the Newark Bears of the Atlantic League, and then the San Diego Surf Dawgs of the Golden League. He was 46 that year, and he walked 73 times in 73 games, and he stole 16 of 18 bases and hit .270. The manager was Terry Kennedy, who had been a major league catcher, and who was heard to mutter, “Go ahead and steal second,” when Henderson was on first. The helplessness was contagious. Henderson was successful on 80.7 percent of his steal attempts, and in 1991 he broke Lou Brock’s alltime record with his 939th steal. He stopped at 1,406. That means he stole 467 more bases after he became the alltime guy. Only 47 players in history have even stolen 467 bases.

Beginning in 1980, Henderson was the A.L.’s leading basestealer in 10 of 11 seasons. He was hurt in 1987 and Harold Reynolds led the list with 60. The day after the season ended, Reynolds’ phone rang. “Sixty stolen bases? Rickey would have 60 by the All-Star break.” Then Henderson hung up.

Henderson bulked up the RBI totals of Jose Canseco, Mark McGwire, David Henderson and Dave Parker in Oakland. He pestered pitchers to the benefit of Don Mattingly, Dave Winfield and Don Baylor with the Yankees. In 1985 Mattingly won the MVP award with 146 RBIs. Henderson scored 145 runs and stole 80 bases in 90 tries. He won his own MVP for Oakland in 1990, when he won the league runs-scored title for the fifth time and slugged .577.

But he also has the record for leadoff home runs, with 81. One day in Cleveland he did it in both games of a doubleheader. He didn’t really think of himself as a power hitter, although his body was a block of granite with a turbocharger, and most people think he would have been a prime NFL running back. When he realized the big money went to the guys who put baseballs in the seats, he worked on his uppercut, and hit 297 homers. It wasn’t like Henderson made the game look easy, because there was too much seething energy for that, but he had little trouble doing what he wanted, and he could apply almost anything to the game.

One of his team flights had a bumpy landing, and then the next one landed without a problem, so Henderson asked the pilot what the difference was. The pilot told him he tried to get the plane low early and let it cruise in smoothly. Henderson began to slide that way. “I wanted to smooth it out,” he said.

And he walked over 100 times in seven different seasons and led the American League four times, including 1998 with Oakland, when he had 118, with 66 steals, and led the league in both categories as a 39-year-old. Mattingly said Henderson would relentlessly campaign for a smaller strike zone, even on pitches down the middle, and eventually wore down the umpires.

Henderson had his contract disputes and his dust-ups with managers, and he was in no danger of breaking consecutive-games records. If he couldn’t be Rickey-to-the-fullest, he wasn’t going to play. But teammates got a kick out of him, loved his authenticity and boundless confidence. When you walked through the back alleys of October, he was a good leadoff man to follow.

Henderson sometimes complained that he didn’t delve into the third person as much as people said. And some of the stories are exaggerated. However, it is true that Tony Gwynn (or was it Steve Finley?) was on the Padres’ bus one day when Henderson boarded and began walking to the back. “Hey, Rickey, you can sit up here,” said the Padre in question. “You’ve got tenure.” To which Henderson replied, “No, Rickey’s got twenty years in.”

When someone mentioned the verse John 3:16, Henderson said, “John might be hitting .316 but Rickey’s hitting .330.” I’m not sure I believe that one. Someone also made up the one about John Olerud, who wore a special helmet after a brain operation, and played with Henderson in Toronto. When Henderson was traded to the Mets, Olerud was there, too. “I played with a guy in Toronto that looked just like you,” Henderson told him.

There was also the guy who said 50 percent of major league players were using PEDs. “Well, Rickey’s not using them,” Henderson replied, “so that’s 49 percent right there.”

Since Henderson played 25 major league seasons and changed teams 13 times, his folklore touched more lives than any other great player’s had. News of his death Saturday was out there on the Internet long before it was confirmed. It was unexpected, which added to the sadness, and it seemed wrong, because Henderson was forever strong and relatively young. Sandy Alderson was his general manager in Oakland, an ex-Marine who saw the way Henderson altered nearly every game he played, who realized that he was watching something no one would ever see again. He came forth with his accolades Saturday, like everyone else did. “He was the best player I ever saw play,” Alderson wrote. Then he ended it with, “Sandy gonna miss Rickey.”

We’ll miss both Rickeys actually, the slow one and the fast one as well. When he was around, somehow the games were never too long.

Great piece