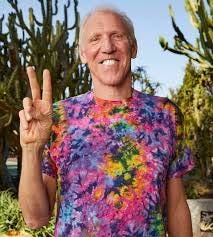

Basketball loses its soul man

Bill Walton's spectacular life of joy and pain ended Monday, after a jam-packed 71 years. He was often repaired but won't be replaced.

Sorting out the best memories of Bill Walton is sort of like looking for Watergate clues in the Library of Congress.

Too much inventory. We’ve been watching him all his life. We knew him when he was UCLA’s happy warrior, at least until someone wanted to take a look inside him, and we knew him when he was a forlorn, injured TrailBlazer, cursed by luck and by those who wanted to cut his hair and his supply lines.

We knew him when he was linked to Jack Scott and Patty Hearst, and when he finally had a season healthy enough to allow him to win a rightful NBA championship, and when it actually happened again, eight years later in Boston, or five years after Clippers doctor Dr. Tony Daly said “He’s accepted the fact that he can’t play anymore.”

None of that is true, of course (especially the acceptance part). We never really knew Walton until he permitted us to, and even at that, we thought it was an act. Can anyone be that maniacally curious, that unabashedly enthusiastic about everything, especially after 37 surgeries and a back problem that immobilized him for years? Apparently so.

Walton felt an almost righteous duty to brighten the days of the people around him, even if he hadn’t made their acquaintance. He was the dad who wrote John Wooden’s best sayings on the bag lunches his kids took to school. He was the basketball analyst who didn’t point out ball screens hut would tell you something interesting about the point guard’s mother or the strength coach’s hobbies or the fact that the assistant coach’s mom downs a shot of Bailey’s at strategic points of the game.

He was the 10-year-old who, once he learned something, couldn’t wait to tell everyone he knew. He was the soul of the game he played and the state in which he lived, fearful of nothing but the day it would all end.

It turned out to be Monday, Memorial Day. Walton died at 71 of cancer, a condition he did not publicize.

“He wasn’t happy until he did everything he could to make everyone around him happy,” said Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. “He was the best of us.”

It happened two days after the Pac-12, his beloved “Conference Of Champions,” observed its final athletic event. At ESPN one night they activated a counter, in the corner of the screen, to keep up with his COC mentions. The Pac-12 has now been vaporized by the love of money, and Walton wrote an anguished letter to the bosses at UCLA, his alma mater, begging them not to go along. Instead the Bruins joined nine other schools as they defected to what Walton called the “truckstop leagues.”

When discussing the Pac–12 on ESPN, usually next to Dave Pasch, he was a veritable Waltopedia. He brought a jar of “Temecula Dirt” to the broadcast table one night to show how it cleansed the skin. He would change shirts at his chair, during a game. One night he and Pasch got cupcakes to celebrate a birthday, and Pasch challenged Walton to eat the cake while the candle was burning. Walton did, on air. He always said his favorite word, and the one that got him in the most trouble, was “yes.”

He was the most unlikely broadcaster you could name. He had a severe stutter, which made it convenient for Walton to stonewall the press when he played. When he decided to try TV, he typically went whole hog and got tutored by the legendary Marty Glickman. A dam broke and a billion syllables flooded America, to the point that Wooden joked he liked Walton better as a silent movie. But Walton spiced it up with his irreverence, with his rejection of broadcaster norms. “That is one of the five worst possessions in the history of Arizona (or UCLA, or Cal) basketball,” he would say. No exaggeration was too outlandish. One night he called John Stockton “not only one of the marvels of basketball or America, but of all of Western civilization.”

The crotchety dads who rolled their eyes, and their sons who laughed and quoted his lines, had one thing in common. Neither knew how good Walton was on the court. But then, none of us did, because of the hollowed-out feet and all the surgeries, which numbered 39 at the time of his death. Walton was a brilliant passer and rebounder who often turned and hit running teammates in stride before his feet hit the floor. He got his points from the lane, and he ran downcourt and occupied the other one and took away your points, too. This is perhaps the only thing Walton would not discuss on the air. He constantly changed the subject when someone praised his basketball. To him, the game was such a fine art that he could never conquer it, and its appeal lay in its teammates. Without them, he said, he might as well play tennis or golf.

One night he watched his talented son Luke lead Arizona to a win over UCLA in Pauley Pavilion. Luke, like Bill, wowed the patrons with passing angles that only he could see. As Bill waited for Luke outside the locker room, someone playfully asked him where Luke got all those skills. “It must have been Greg Lee,” Bill said, referencing his closest friend and UCLA teammate.

Walton was an employee of the NBA for 14 years and started only 117 games, playing 468. Four times he played over 58 games in a season. Two of those years were championship years.

“Eventually I ground my lower extremities into dust,” he wrote in his autobiography, “Back From The Dead.”

Walton’s ever-present bicycle was the balm for his feet. He thought the perfect day consisted of 100 miles behind the handlebars. It also soothed his mind, in the same way that the Grateful Dead was the soundtrack of his life, and its members joined the endless list of his best friends. “My bike is my medicine,” he told the Wall Street Journal. “I”m always sick of something or somebody, and I know that when I go out on my bike, my bike makes me happy.”

In the second paragraph of his book, he puts himself back into the days when he literally lived on the floor of his house. “If I had a gun, I would use it,” he writes. He fought his way back to the point where he could take a bike ride in the neighborhood. At the end of it, a skateboarder crashed into him, breaking his pelvis and sacrum. Back to Square One and the darkness.

He found another life, of course, and no doubt he expects yet another one is waiting for him after Uncle John’s Band called him home on Monday. Until then, the greatest wish, for those who survive, is for them to find someone to love them half as much as Bill Walton loved basketball, and life itself.

Brilliant. Like a Walton pass.

Excellent, excellent piece. You well covered the complexity of Bill Walton. He was a great player (and I had not realized how few NBA games he started) and evolved from much "darkness" into a guy I pointed out to my son because of the fun he brought to his basketball commentary. Thanks for this.