Bill Walton and the pursuit of everything

ESPN's four-part documentary was poignant and inspiring

ESPN’s recent layoffs generally spared the clowns and skewered the professionals. The network will be diminished without Jeff Van Gundy and Suzy Kolber, in particular. It already is diminished by the parade of empty opinions and high-volume hypotheticals that dominate its mornings and afternoons. Most of those actors will continue their noise pollution, unfortunately.

It’s also unfortunate that we tend to tar ESPN with that particular brush, and fail to appreciate just what sports was like before it showed up on our non-smart TVs, with Jim Simpson and Tom Mees. It was not always the Worldwide Leader of Hot-Dog Eating. It made college basketball a national sport, conducted several worthwhile investigations, and helped bring about the first true college football playoff.

It also pioneered the sports documentary, most notably the 30-for-30 series.

Those who were trying to escape cable news reruns or flag-waving semi-entertainment Tuesday night could stumble upon “Fantastic Lies,” the meticulous and shattering story of the way the Duke lacrosse team was railroaded by a misbehaving district attorney and convicted in advance by pressure groups and the assumptions of Big Media. It is more damning now than it was 15 years ago.

And, last week, ESPN finished up its glorious four-parter on the life and times of Bill Walton, entitled “The Luckiest Guy In The World.”

The point is that Walton, by anyone else’s standards, was anything but. He lost most of his pro career to persistent foot injuries that eventually forced a fusion operation. He lost most of his money and, temporarily, his broadcasting career because his back cruelly rebelled against him and forced another fusion. The fact that Walton can walk is one reason he considers himself so lucky, because it is no routine thing. The chair that he uses for his sideline basketball broadcasts looks like an ergonomic throne.

One of the many poignant moments was the story about Luke Walton, the former NBA coach and Bill’s most accomplished son in basketball terms, calling up Bill and offering him money to get through all that. Walton was reduced to desperate tears. Yet, in the end, there was triumph, because Walton was able to win a second championship in Boston to go with the one he won in his prime, nine years before that, in Portland.

And even though some stiff-collared folk might scoff at Walton’s meandering commentary on college games, it’s a near-miracle that he’s able to make all those trips and sit through all that, or that he is able to speak so clearly, thanks to training by famed broadcaster Marty Glickman that put his stuttering to rest.

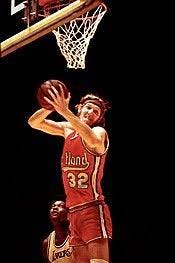

Although the documentary half-dismissed his ESPN career, it did point out why Walton doesn’t obsess on “ball screens” and other buzzwords of the commentariat. He feels the X-and-O side of basketball is too elementary to deserve explanation. Today’s version of Walton, in terms of big-man instinct, is two-time NBA MVP and current NBA champ Nikola Jokic, who shrugs and says, “If they play off me, I shoot. If they guard me, I pass.” In the documentary, a new generation sees Walton making those pinpoint outlet passes, often before his rebounding feet hit the floor, and sees him passing out of the post and from the foul line. He was a Jokic who could also capture games with his defense. There is little question, among those who witnessed him, that he would have been one of the very best players of alltime, given the health that blessed Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Michael Jordan.

But the best parts of the shows were the time spent with Walton himself, the recapture of his uniqueness. I happened to be at the 1986 NBA Finals in Houston, when Walton was coming off the Cetlics’ bench and battling Hakeem Olajuwon straight-up with his gleeful dedication. During a timeout in The Summit, they played Robert Palmer’s rollicking “Addicted To Love,” and it seemed to be the perfect soundtrack to what Walton had become: “You like to think you’re immune to the stuff, oh yeah/Closer to the truth is that you can’t get enough/Might as well face it, you’re addicted to love.”

And that’s what Walton was. That’s why he was at the front of the line of the Deadheads, going anywhere on the globe to see a Grateful Dead concert. He knew Jerry Garcia and the gang but he preferred to watch the concerts from the audience. The Dead’s music is largely the soundtrack of “Luckiest Man,” and they were made for Walton. If the song needed to be 45 minutes, it was. If the show needed to be four hours, it was. There would be no limit to the pursuit of the things one was born to pursue.

Walton was asked during the winter if there was one favorite word in his life. He replied that it was “yes,” because he had said it so often, and it remained his favorite even though it led to all sorts of excesses. He couldn’t just be a supporter of “sports activist” Jack Scott, he had to let him live in his house. He couldn’t just dabble in a more nutritional diet, he had to devote himself to fruits and nuts, and try to play pro basketball as a skeleton.

Through it all he retained a lascivious fascination. On the broadcasts, he researches the family backgrounds of the players, the parents of the players, the strength coaches. When long-suffering partner Dave Pasch dared him to eat a cupcake on the air with a candle burning, Walton did so. “Have you ever been in a volcano?” Walton might ask. But there was always a sly send-up of normal announcing, deep underneath the esoterica.

When he worked with Ralph Lawler, the Clippers were terminally dreadful. One night Sean Rooks came off the bench to hit an 18-footer and pull the last-place Clippers to within 20 points of their opponent. “Ralph,” Walton would bellow, “where would this team be without Sean Rooks?” In last place, of course.

Another night, Hubert Davis of Washington was having one of his best pro games ever at the Clippers’ expense. “Ralph,” Walton observed, “I think the Clippers need to realize that Hubert Davis is right-handed. And probably will be for the rest of the game.”

Walton also scorns deep-dive analysis of Pac-12 games because they are, after all, Pac-12 games, despite his “conference of champions” shtick. (Advisory to the serious curmudgeons among us: Walton did not really think nine Pac-12 teams deserved to be in last year’s tournament. He is not stupid.) But when the score is tied and there is a time out with five seconds left, and Pasch needs his analyst to actually come up with a suggested plan, Walton comes up with one every time, along with a couple of options.

The documentary shows Walton visiting his mother, and his Helix High coach in San Diego, the widow of best friend Maurice Lucas, and his teammates from the Blazermania years, when no team was more beloved by any fanbase. Hilariously, it spends time with Walton’s four boys, and how they are as bemused as you are by what he might say. When Walton says the seventh man on the Utah Jazz is the best player he’s ever seen, he is not playacting. He has also said the same thing at home.

At one point Walton is walking around his old Portland neighborhood, and he comes upon a park where he used to shoot and dunk, sometimes even on game days. Here, he addresses a few kids who happen to be there shooting, maybe junior high age. They have no idea who this tall person is, exhorting them to do their best, volunteering to be their rebounder. Considering the times, they might have been forgiven for a furtive cellphone call to the local constabulary. Instead they sense that the old man comes in peace, and they keep playing, keep listening, and eventually Walton moves on.

ESPN’s top-floor decision makers should watch that sequence again and learn from it. Some truths are best delivered unsaid.

Nice article Mark...REALLY enjoyed the series and have always just admired his passion for life. I met him briefly in a doctor’s office in the early 90’s and he was really engaging and quite ‘loquacious’ about Chapel Hill when he learned I went there.