Fernando captured L.A. in record time

The death of the Dodger lefthander reverberates far beyond the stadium.

If you remember how young Fernando Valenzuela made you feel in 1981, you’re probably grasping at handrails and searching for Metamucil today.

No one had ever been the Rookie of the Year and the Cy Young winner in the same season. No one ever captured Los Angeles so quickly and unconditionally. Valenzuela was a promising rookie at the end of 1980, and Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda would regret the final game of that season, when he picked Dave Goltz over Valenzuela to pitch a game they had to win against Houston. The kid had been scoreless in his 10 games of relief. The Dodgers didn’t win.

Almost 13 months later, Lasorda never budged in the Dodger Stadium dugout and watched Valenzuela struggle to find his bearings in World Series Game 3 against the Yankees. Valenzuela still won, 5-4, and threw 147 pitches in the act. He would have pitched Game 7 of that World Series, but the Dodgers won in six. He was 21 years old, and he already knew that pitching, and winning, was an affair of the heart.

In between, Valenzuela superseded an ugly baseball work stoppage to become the most charismatic Dodger since Sandy Koufax, and a cultural figure that went beyond the sport. “When he pitched it was a religious experience,” Vin Scully said. “It really had little to do with baseball.”

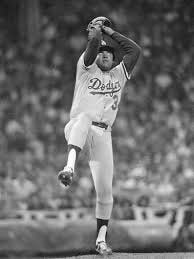

Valenzuela, whose death at 63 Tuesday night rocked the baseball worlds of at least two nations, was a stocky fellow who lifted his eyes to heaven during his delivery, and his pitches arrived at pedestrian velocity but with dancing feet. His screwball was the most famous weapon, but he was a savant in terms of changing speeds and detecting weaknesses. He also had fun. When he was removed in the chill of Game 5 of the National League Championship Series, a winner-take-all game in Montreal, Valenzuela took two fingers and pantomimed smoking a cigarette, as the vapor from his breath came forth. Then Rick Monday won the game with a homer off Steve Rogers. So Valenzuela was a talisman as well as an artist.

He pitched nine postseason games all told and had a 1.78 ERA. He won his first eight games that year. Not decisions, but games. Not parts of games, but all nine innings, every time. On May 18 he finally lost, to Philadelphia at home, but gave up three hits in seven innings. He ended the season with a three-game losing streak, thanks to poor run support, but finished 13-7 and led the league in innings and strikeouts. He also pitched 11 complete games. Along the way the Dodgers drew 2.3 million fans. That’s in 56 home dates.

After each game Valenzuela did mass interviews, speaking Spanish, with broadcaster Jaime Jarrin interpreting. Jarrin had already established the Dodgers in L.A.’s Mexican community. Valenzuela always knew more English than he let on, but he preferred to do interviews that way because he didn’t want to slip up. It was also a way of standing up to the establishment, which rarely had provided interpreters to other Latino players. That made Valenzuela even more endearing.

“He made Mexican-Americans feel a little more Mexican,” said Tomas Benitez, an actor and community cultural worker, when Valenzuela was inducted into the Shrine of the Immortals, the Baseball Reliquary’s Hall of Fame for the game’s true characters, in 2006.

“Back then Mexicans and Mexican-Americans had their tensions, over shared space and the like. But they all came together in the bars, listening to Jaime and Vin on the radio in the backyard, whenever Fernando pitched. He made us proud to be a Mexican.”

For the next six seasons Valenzuela was a constant. He finished in the top five of Cy Young voting three other times, and pitched at least 250 innings each season through 1987. In 1986 he was 21-11, winning 20 for the first and only time, and went the distance 20 times. That eventually caught up. Valenzuela began having shoulder problems in 1988 and missed the Dodgers’ run through the World Series. But in 1990 he pitched a no-hitter against the Cardinals. He bounced around the majors through 1997, and his final game was in Mexico, at age 44. Then he joined Jarrin in the Dodgers’ broadcast booth. Valenzuela also won a Gold Glove and was a .200 lifetime hitter with 10 home runs.

In the end Valenzuela left with a 173-153 record, with 2,930 innings and a career ERA of 3.54. Certainly you need better composite numbers to get to the real Hall of Fame. But if the Hall is all about the folklore of baseball, and about players who sold tickets and brightened lives and made an impact, Valenzuela definitely belongs. Those who heard the stadium vibrate when he came to the mound, as the stadium soundmasters played Abba’s “Fernando,” know where he fits in the history of both club and city.

Valenzuela also made a star out of Mike Brito, the scout in the white hat who was always behind the plate, holding up his radar gun as the cameras shot Valenzuela from center-field. Brito did much more than that, signing Yasiel Puig, Julio Urias and dozens of others. He saw Valenzuela, the youngest of 12 children, throwing in a game in Silao, Mexico, and signed him for $120,000. But when Valenzuela was pitching in Lodi, his fastball wasn’t holding up and Brito knew he needed another pitch. Fortunately he had just the pitch and just the guy to teach him.

Bobby Castillo had been released by the Royals as a third baseman. Now he was pitching in a semipro game in East L.A. Brito also played in those games at times, and when he stepped in against Castillo, he screwed himself into the ground trying to deal with his screwball. Brito recommended Castillo to a club in Mexico, and when Castillo succeeded there, the Dodgers signed him. And when Valenzuela struggled in the minors, Brito sent Castillo to teach him the pitch that unlocked all the doors.

The rest came from deep inside. Valenzuela never tipped his hand, never reacted to glory or adversity, never seemed anything but at home on the mound, especially in the early, rock-star days when Castillo and Jarrin were basically his Secret Service, and he had to eat and drink and shop and live in near-isolation.

There was an ominous tone to the way Valenzuela abruptly left the broadcast team a few weeks ago, and news of his death provided more of an ache than a shock. It happened three days before another Dodgers-Yankees World Series. It also happened in a time when it takes a half-dozen pitchers to get the 27 outs that Valenzuela viewed as an obligation.

It wasn’t that long ago, was it, when Valenzuela was the new kid in town? No, not really, but he deserved to get old, too. It would have been another shared experience.

Terrific column. A fitting farewell to a Dodger legend.

Thanks. How sad that in today’s game there never could be Fernandomania. The hubbub around Ohtani is close but without the profound cultural impact you describe. We’ve seen our last Maddux or Fidrych or Ferguson Jenkins, right? The list goes on and can be recited back to the dawn of baseball time.