From Naismith to Nesmith, it's a fast-forward game

No lead is safe and no conclusion is either, as the Pacers are proving.

In 1891, James Naismith was given 14 days to invent a game that would calm down his class at the Springfield (Mass.) YMCA.

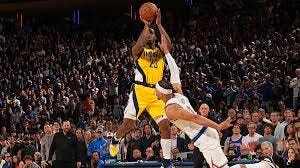

In 2025, Aaron Nesmith needed four minutes to turn Madison Square Garden into the world’s biggest bookless library.

The original game and its descendant have far less in common than the Motel T and a Rivian. Nesmith would surely have knocked the bottom out of Naismith’s peach basket in the fourth quarter Wednesday night. He drilled six of seven 3-pointers in the final 4:45 of the period. His first one cut New York’s lead to 12 points, and then Nesmith went on a rainmaking frenzy, hitting four bombs in the space of two-and-a-half minutes, from the right corner and the left wing and straightaway. When Tyrese Haliburton launched a last-second shot that hit the heel of the rim, rose into the Garden ether and then fell through the hoop, Indiana had tied the Knicks, and then overcame a four-point deficit to win, 138-135, in overtime. That was good for a 1-0 lead in the Eastern Conference Finals, which resume Friday night.

Reggie Miller had a similar flurry against the Knicks in a playoff 30 years ago, and was sitting at the TNT broadcast desk, very well-preserved, and pointed approvingly at Nesmith on Wednesday. But it’s difficult to remember such a prolonged spree in what seemed such a lost cause. In the previous century, players who assumed such an offensive burden were known as “gunners.” They were selfish, and increasingly scorned. Even now you hear the term “heat check,” but only when the shooter misses. Despite all of Indiana’s assembled shooters, there was not one peep of objection when Nesmith kept rising up. He wound up with 30 points, a career high, and 20 of them happened in that stretch run. No one had ever cashed six 3-pointers in the fourth quarter of a playoff game.

“It’s probably the best feeling in the world for me,” Nesmith said. “I love it when that basket feels like an ocean, and everything you put up there feels like it’s going in.”

Josh Hart of the Knicks said they began “playing not to lose,” and Karl-Anthony Towns said they “took their foot off the gas” when they built the big lead, which was remarkable considering they went on a 10-0 run when Jalen Brunson drew his fifth foul. They should have known better. Twice they wiped out Boston’s 20-point leads in the Eastern semifinals. And they also should have known Indiana’s knack of beating the clock. Only four times has a playoff team overcome a seven-point deficit in the final minute of regulation, or in overtime, since the league began keeping play-by-play data in 1998. Indiana has now done it three times in this postseason alone.

And the Knicks weren’t immobilized during all this. They scored 12 points in the final 4:55. When Towns converted a layup with 42 seconds left, the Knicks led by eight. They could scarcely have asked for more from Brunson and Towns, who combined for 78 points on 26 for 42 shooting. Even though they had a major defensive hiccup in overtime, on an in-bounds play that became a layup by former Knick Obi Toppin, the Knicks didn’t lose this on defense because they watched Nesmith take shots that, until very recently, they would have preferred him to take. Maybe after two of those buckets, they could have been more attentive, because, these days, you can’t just assume that a hot shooter will flame out. Confidence and carte blanche aren’t easily overcome, when taken together. In fact, coaches only berate their shooters when they don’t shoot enough. Golden State’s Steve Kerr said his offseason project with Brandon Podziemski was to overcome his reluctance to launch.

There are a lot of Nesmiths in the league these days, several of whom are Pacers. This one was marooned on the Boston bench until last season, when the Celtics put him in a package that brought Malcolm Brogdon. The Pacers were in the middle of a redo, supervised by coach Rick Carlisle, and they liked Nesmith’s strength, defense and basketball sense. He was so inspired that he volunteered to play for Indiana’s NBA Summer League team, usually reserved for the rookies.

This was Nesmith’s third season in that system, and he responded by joining the 50-40-90 club, reserved for 50 percent field goal shooting, 40 percent from three, and 90 percent from the foul line. No one else in the league who played at least 40 games did that. In the playoffs he’s a 53.8 percent deep shooter.

Nesmith, like the Pacers, has had to make his own case. He wasn’t getting much notice at his Charleston, S.C. high school, but a stellar AAU season in Charlotte brought the recruiters. Some of them were from the Ivy League, thanks to his classroom work. Nesmith went to Vanderbilt and was in the midst of a 52.2 percent 3-point season when he got hurt.. The Celtics picked him 14th in the first round anyway.

This was the third full season for Nesmith, Haliburton, Myles Turner, Bennedict Mathurin, Andrew Nembhard and T.J. McConnell. Pascal Siakam came from Toronto last season to give Haliburton some All-Star company. “We’ve been through every situation together,” Haliburton said.

Carlisle has been the coach for the past four seasons, in tandem with general manager Kevin Pritchard. He managed the tempo in most of his other coaching spots and, when you have Dirk Nowitzki ringing the bell at will and Jason Kidd running the show, that’s what you do. Dallas won the 2011 NBA championship that way.

Fourteen years later Carlisle is commanding the Pacers to run indiscriminately and shoot when the spirit moves them. His roster tells him that it’s time to play fast. Better to keep the winds of change at your back, because Naismith’s game isn’t likely to stop at Nesmith.