It’s called “The Book Of Joe,” by ex-Cubs/Rays/Angels manager Joe Maddon and Tom Verducci, a warm and passionate memoir of a benchwarmer’s bumpy journey to major league managing history.

It was all set to end inspirationally.

Then June 7 happened.

The Angels were 27-17 on the morning of May 25, surprise leaders of the American League West by one game. The new bullpen that general manager Perry Minasian gave Maddon was working. Guys who hit home runs got to wear a cowboy hat when they returned to the dugout. The Angels were young and happening. Why go watch the Dodgers, whose nightly romps had hypnotized the N.L. West, when the real story was in Anaheim?

Then caame 12 consecutive losses. When the record reached 27-29, Minasian dropped by Maddon’s house in Long Beach and fired him. The Phillies had just fired Joe Girardi and were winning with interim manager Rob Thomson. That wasn’t the sole inspiration, because Maddon was nearing the brink anyway, with a GM who didn’t hire him. But it happened, and the Angels got a lot worse before they finished 73-89.

Quick, get me rewrite.

Maddon’s firing provided “The Book Of Joe” with a closing chapter and a news hook. Maddon revealed that Minasian and his analytics henchman Alex Tamin had their own lockers in the clubhouse, just off the coaches’ room. So much for spontaniety and the concept of an inner sanctum.

Tamin had worked in the Dodgers’ analytics department before he joined Minasian in Atlanta. It is instructive to note that the Dodgers have continued to win 100-plus games without Tamin, and the Angels have continued to miss playoffs and suffer losing seasons with him. Interference from Minasian and Tamin, especially pre-game and post-game visits to Maddon’s office, caused tension that Maddon released when he was fired. He called the firing “liberating” and said Minasian & Co. “did not read the tea leaves properly.”

Maddon saved some ammo for the book. In this final chapter, he recounts that Minasian ordered him to remove Mike Trout from a lopsided May 9 victory over Tampa Bay. “That broke a sacred code,” Maddon said. But so did the removal of Maddon’s jurisdiction over his bullpen. Minasian and Tamin began telling the manager who was available on any particular night, based on a 30-day algorithm that Tamin had devised. The relievers themselves were generally stunned to learn, pre-game, that they might as well go home.

Such things aren’t uncommon. They are just suppressed, because of the what-happens-here-stays-here mentality of a clubhouse. Managers get fired every year and put up with similar intrusions every year, from GMs who think this is just a Strat-O-Matic game with vastly overpaid cards. Most of them nod their heads, thank everyone for the “opportunity,” and then wait for the next job, and contract, to arrive. Maddon, 68, did not, which means he’ll probably get another MLB managing job when the catcher’s mask is outlawed. At last report he was unbothered by this, attempting to set daily personal records for most consecutive days of golf.

So who knows if this quirky, inspirational baseball life stops here? Most likely, this won’t be Maddon’s final book. He is obsessively curious about all kinds of things, has a surgical way of connecting with everyone he meets, and, ironically, was an early devotee of progressive baseball. He took defensive shifts to the next level, had no problem bringing in relievers in the middle of a count, and could spot talent. I remember 2022, when he was part of an extraordinary Angels’ coaching staff and management team. He had a statistical grid for each at-bat, including the prophetic category, “0-2 to 4-2.” In other words, if you could turn an 0-2 count into a walk, you had the fearless plate discipline and visual discernment that is now the rule in every major league dugout.

But Maddon’s people skills, and his constant T-shirt messaging, obscured how fierce he could be. He got so upset at the Double-A Midland team he was managing that he cut out help-wanted ads from the newspapers and wallpapered the clubhouse bathroom with them. When he began managing the downtrodden Rays he had them playing exhibition games against the Yankees and Red Sox as if dinner was at stake. The collisions and brawls, in Maddon’s mind, gave the Rays the identity they’d never had. In three years he got the Rays into the World Series even though they’d never won as many as 70 games in a season before.

In between the bromides like Do Simple Better, The Process Is Fearless and Embrace The Target, Maddon shares the absurdities and the poverty of baseball life on the fringes. His relationship with cars would be a movie in itself, particularly the 1969 Volvo that he drove, or tried to, when he was playing for the Boulder (Colo.) Collegians. It had a coil wire that would immobilize the car whenever it got out of positon, so Maddon had to jiggle it until it worked, sometimes in the middle of intersections. “Then, all of a sudden, it decided not to go into reverse,” he said, and it never reversed that decision.

He is a strong advocate for managing in the minor leagues or at least putting in development time, and the success of Thomson and Atlanta’s Brian Snitker supports that. And back then, Maddon was allowing teenage pitchers to throw nine innings if they could.

His world was full of reprobates and baseball dictators and just plain characters back then, including manager Moose Stubing, who told his team, “There’s 25 of them and one of me. So I don’t have to get to know you. You have to get to know me.” He learned human engineering on a granular scale, a skill he began picking up as a plumber’s son in Hazleton, Pa.

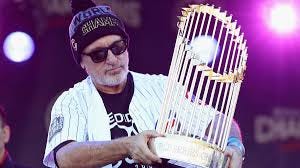

But as Maddon slowly rose in the business, he ran into different barriers and tougher relationships to forge. Even after he managed the Cubs to their first World Series title in 108 years, and made sure everyone knew it was a fait accompli from the moment he took the job, he couldn’t stay. General manager Theo Epstein wanted more organization, more meetings, more regimentation when the Cubs began to lapse, which meant he no longer wanted Maddon. The manager who had provided the Cubs with the thrill of several lifetimes was gone three years after Kris Bryant’s final thorw across the diamond to Anthony Rizzo (they’re gone, too).

The book is full of introspection and a good bit of regret, so maybe Maddon will someday wish he hadn’t shined a light on Angel conversations that are normally confined to darkness. More likely he’ll regret how he bit his tongue the first time he saw the steering wheel being removed from the dugout, and placed upstairs in hands that never caught a baseball.

Terrific read, Whick.