Long ago, the Olympics didn't need money to win us over

The 1924 Olympics in Paris was famous for Chariots of Fire, but DeHart Hubbard had a big meet too.

The Olympics returned to Paris Friday for the first time in a century. That one became known as the Chariots Of Fire Olympics, thanks to the 1981 film, forever associated with soaring music by Vangelis and breathtaking shots of Harold Abrahams (played by Ben Cross) and Eric Liddell (Ian Charleson) reaching to the very basement of their souls to win gold medals. It might have been the greatest sports-based movie ever, and yet 1924 had so much more fire than that, if not as many chariots. History overflowed. It always seemed more significant, in the Games, when it was brought by athletes from the real world.

Liddell was a missionary who died at the hands of the Japanese, in China, when he was only 45. Abrahams was a law student. He had a professional coach, Sam Mussabini, who was banned from the stadium and, according to the film, had to watch from a nearby residence.

But then Al Oerter, the four-time discus gold medalist from the U.S., was a computer programmer, and Bobby Morrow, who won two sprint gold medals in 1956, found it more profitable to retire as a farmer two years later.

In 1936 Jesse Owens won four gold medals in front of Adolf Hitler in Berlin, perhaps the most brilliantly defiant moment in Olympic history. When he tried to parlay that into endorsements, his amateur status was revoked and he could no longer compete for the U.S. This led to various, demeaning pursuits, including a race against a horse. “You can’t eat four gold medals,” Owens explained.

Today’s Olympic champions get as much money as they need. Michael Phelps and Carl Lewis spent 12 years apiece winning medals. No one begrudges them, particularly since the Soviets and East Germans were subsidized by their governments. If the Olympics are truly the greatest sporting competition in the world, the greatest players should be there. Still, the Olympics used to be famous for the way it accommodated life’s underdogs, like Billy Mills, the Sioux runner who never had a pair of new shoes until the night before he won the 10,000 meters in Tokyo, 60 years ago.

Obviously Usain Bolt, who fished out the title of World’s Fastest Human that Ben Johnson left in a drain and elevated it to unimaginable heights, did nothing but glorify all the Olympics that he dominated. But should LeBron James and Coco Gauff be the flag-carriers for the U.S. team? Their fellow teammates thought so. They elected them. But Diana Taurasi was on the boat, too. She’s won five gold medals for Team USA, the first one 20 years ago. And there’s Matt Anderson, the outside hitter for the men’s volleyball team, making his fourth Olympic trip at 37.

The 1924 Paris Olympics was famous for Paavo Nurmi, the Flying Finn, winning 1,500 and 5,000 meter runs in an hour’s time, and taking five gold medals overall. Johnny Weissmuller of the U.S. took home three swimming golds and another for water polo. Harold Osborn became the first to win the decathlon gold and another event, the high jump.

But the real breakthrough, one worthy of a film in itself, came from DeHart Hubbard.

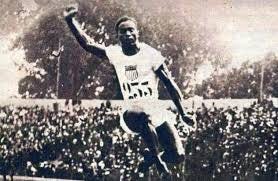

Hubbard was a distinguished high school athlete in Cincinnati and somehow won the attention of an influential Michigan alum, who knew of a program that would provide scholarship money for the person who signed up the most subscribers for the Cincinnati Enquirer. The alum got his friends, one of whom was baseball executive Branch Rickey, to pitch in, so Hubbard wound up in Michigan and became a sensation. He won four Big Ten track titles and qualified for the Olympic team in the long jump and triple jump, and also in the 100 meters and high hurdles, although he was banned from those events. Hubbard was Black, and on the boat to France he wrote his mother a letter: “I’m going to do my best to become the FIRST COLORED OLYMPIC CHAMPION.” Then he underlined “Colored.”

It didn’t start well. Hubbard hurt his heel on the board during one jump, fell backwards when he landed on another. He barely qualified for the finals, and then he learned that U.S. teammate Robert LeGendre had broken the world long jump record while he competed in the pentathlon. That had been an obsession of Hubbard’s, and now he had to clear his head.

Hubbard was on crutches before the final. On his final jump, he asked almost everything from his toes, and cleared 24 feet, six inches, which wasn’t a record but did win gold.

A couple of years later Hubbard hurt his knee playing volleyball, which took him out of the 1928 Olympics in Amsterdam. He wound up owning the Cincinnati Tigers of the Negro Baseball League and worked with Owens in the Federal Housing Administration in Cleveland.

There are no more Miracles on Ice or Giant Leaps by Bob Beamon, although there’s always a chance you’ll see the equivalent of the injured Derek Redmond, being helped across the 400 meter finish line by his dad, Jim, in 1992. Again, that’s just as well. But the forgotten jumps of DeHart Hubbard also need to be commemorated, as part of the Olympic soul. They can be capitalized and underlined, too.

In 1964, USA's Bob Hayes won Tokyo Gold.