Mourn Bill Russell without comparing him

It is difficult to imagine anyone getting the Last Word on Bill Russell, but Michael Jordan tried.

Jordan said his Bulls were going after Russell’s records. Russell replied, “Which one?” He reminded Jordan that his Celtics had won eight consecutive NBA championships in a day when there were only eight NBA teams. Which meant, he said, that Jordan couldn’t have assisted John Paxson on the Finals-winning jumper in 1993, because Paxson, or his equivalent, wouldn’t have been good enough to make a roster.

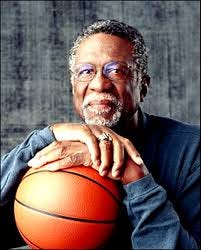

Russell died Sunday at age 88. He retired when he was 34 but he remained basketball’s patriarch until the end. Today’s walking conglomerates sought out Russell, were humbled by his presence, motivated by his approval.

Imagine if they’d seen him play.

It is hoped that this period of commemoration will erase all doubt about Russell’s actual performances, which he found less important than the things he did elsewhere. His game was part Dikembe Mutombo, part Tim Duncan, part Bill Walton, except he pioneered all the things that made them so distinguished. He blocked shots when the NBA didn’t consider it a statistic, and he fired outlet passes to the other Boston Celtics who basically ran their way to all those titles. He was also a visionary passer in the half-court. As Bob Cousy said, the Celtics still had himself and Bill Sharman and other fine players before Russell showed. They tried to run. “But when Bill came, he got us the ball,” Cousy said.

Russell and Team USA won an Olympic gold medal in Melbourne, late in 1956. He went straight to Boston. On Dec. 22 he got 16 rebounds in his 21-minute debut. Four games later he had 34 rebounds. The Celtics won the NBA championship in the spring, against St. Louis, “where I was the only black man in the building,” Russell recalled. Coach/general manager Red Auerbach had already said he didn’t care if Russell scored a point, but Russell averaged 16.1 points for his career even though he really couldn’t shoot. But he won the first of five rebound titles in that rookie season and averaged 22.5 overall.

Russell also averaged 42.7 minutes in his final season, when he was the Celtics’ player-coach and, of course, won his 11th title, with Don Nelson somehow bouncing in a late shot as Jack Kent Cooke’s balloons stayed trapped against the Forum ceiling.

None of this was a shock. Russell’s San Francisco teams won two NCAA championships and 55 consecutive games. In the 1956 Final, Russell had 26 points and 27 rebounds and held Iowa’s Bill Jack Logan, who had scored 36 in the semifinal, to 12.

The Rochester Royals had the first pick in the draft but said they couldn’t afford Russell, who had turned down a $50,000 offer from the Harlem Globetrotters. They took Sihugo Green (they’re now the Sacramento Kings, and still doing such things) and that left St. Louis with the second pick. Ed Macauley was the Celtics’ center and a future Hall of Famer, and Cliff Hagan would join him there. Russell also made it known he wasn’t interested in St. Louis. Auerbach dealt Macauley and Hagan to the Hawks for Russell, a move that was not universally applauded. After all, who blocks shots? It’s against all defensive principles.

Now the blocked shots take up most of our memories of Russell, probably too many. Researchers estimate that Russell and Wilt Chamberlain probably blocked between six and eight per game. The official record average, for a stat that was only kept from 1974 on, is 4.3 by Hakeem Olajuwon. But Russell did much more than that. He was incredibly athletic, an Olympic-caliber high jumper and hurdler after all. His wingspan was formidable before anybody actually measured such things.

He also initiated things that have become bromides. Start playing defense before your man gets the ball. Block shots that your teammates can handle, not the ones that land in a spectator’s popcorn (as Chamberlain did). Russell also explained his longevity by pointing out that he only ran in straight lines down the middle of the court. His mileage, he said, was more important than his age.

Auerbach left the coaching seat to Russell in 1966, although Russell didn’t often sit. That Celtics team finally came up short against Chamberlain and a historically powerful Philadelphia team. But the 76ers were nearly as good the next year and Boston beat them in Game 7 of the Eastern Finals, as Chamberlain had four field goals in 48 minutes against Russell.

Russell was 84-58 against Wilt’s teams overall, and Chamberlain averaged only 22.5 points against Boston in playoff games. The myth is that Russell’s teammates outclassed Chamberlain’s. In truth they were better than anybody’s teammates, but Paul Arizin, Tom Gola, Chet Walker, Hal Greer, Al Attles and Billy Cunningham all played with Wilt and lost big series to Boston, and they’re all in the Basketball Hall of Fame. If there was a tipping point in 1967 it was the overwhelming presence of power forward Lucious Jackson. Besides, the other Celtics were better because Russell made them that way.

Russell’s daughter Karen says her dad probably didn’t think much about heaven because he couldn’t have imagined anything more than playing with those Celtics. Although Russell had a strict definition of friendship and didn’t apply that to teammates, he believed strongly in bands of brothers.

He made an AT&T commercial with “Ron,” and the two of them took turns needling each other. “I made Bill what he is today,” Ron said. “Nothing.”

Ron was Ronny Watts, the last man on the Celtics’ bench who was basically a human version of Auerbach’s victory cigar. Thanks to his celebrated friend, Watts got more than a few minutes of fame.

Yet Russell preferred walking alone. He was short with a press corps that he considered silly. He smoldered, as anyone would, when he and the family found their dream house in Reading, Mass. and then saw intruders scrawl racial slurs on the fence and leave human feces in their bed.

The cops told Russell the damage must have come from raccoons. Russell then told them he would get a gun permit the next day. Amazingly, Karen recalled, the raccoons never returned.

It’s why Russell rarely returned to Boston after he retired, and only had his jersey retired in 1972 with the assurance that no fans would attend. The Celtics had a “real” tribute for him in 1999.

In 1964 Russell was up front when the players threatened to boycott the All-Star Game, in Boston. Elgin Baylor and Jerry West joined Russell in an 11-9 vote to hang up their sneakers. Fifteen minutes before the game, and under immense pressure from ABC, commissioner J. Walter Kennedy agreed to give the players a pension plan.

In 1961, the Celtics played an exhibition game in Kentucky, but the black players were told they weren’t welcome at a restaurant. The game didn’t get played.

In 1963 he ran an integrated basketball camp in Mississippi after Medgar Evers was assassinated, and he led a sit-in and other protests during Boston’s bitter period of school desegregation and busing. Why should he stick to sports? Sports never stuck to him.

He found it unfulfilling to continue with the Celtics, but he did coach Seattle and Sacramento. He devoted the rest of his life to mentoring, activism and mostly golf, where he coaxed his handicap down to seven but got frustrated when it stopped there.

Russell disdained basketball numbers and would have shaken his head and cackled over all the debates about the GOAT (Greatest Of All Time). In his mind there was only one candidate. If acronyms are your preferred communication method, call him the COAT, the Champion Of All Time. He, Magic Johnson and Steph Curry are the three players since the late 50s who have turned basketball into something that it wasn’t before.

On Sunday, NBA commissioner Adam Silver called Russell the hoop version of Babe Ruth. It’s a flawed comparison, as all of them must be, but it does carry a legitimate warning. Don’t bother waiting for the next one.

Great piece!