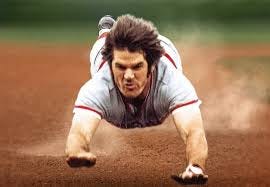

Rose's only home was at the plate

The Hit King dies, at 83, unable to outlive his punishment, but alive in the minds of his older fans.

Pete Rose lived long enough to watch baseball embrace its own hypocrisy, to watch the game make peace with Draft Kings and FanDuel right out there in the sunshine without splitting up cash in back alleys, misbehaving in the open just like he did.

The irony didn’t feel like triumph to him, because he was too plugged into his own situation. He wasn’t a Big Picture guy. Again, in July, he was selling his autographs in a narrow warren off Main Street in Cooperstown, maybe a couple of ground-rule doubles away from the Hall of Fame, where he belonged.

He also outlived much of the Rose Generation. Today’s youths, to the extent they recognize him at all, recognize him as a puffy old man who keeps trying to be some sort of one-man Innocence Project, to reinstate himself into MLB and the Hall despite the fact that he unabashedly violated its First Commandment. He bet on games, and the over-and-unders and prop bets that surround us today do not give him absolution.

It is hard to explain what a national furor this became in the late 1980s, when the gumshoes finally got him, when 51-year-old commissioner A. Bartlett Giamatti banned him from the game in 1989 and then died eight days later. Rose thought Giamatti had pledged he would not mention gambling in the suspension statement, but Giamatti did. Baseball’s rules allowed Rose to ask for reinstatement in 1990, but Giamatti made it clear that this was a life sentence. Subsequent commissioners Bud Selig and Rob Manfred resolutely maintained it, and the Hall of Fame never put Rose on the ballot. Not even the Veterans Committee, composed of players and executives and a few media types, has been permitted to rule on Rose.

He died Monday in Las Vegas, at 83. He had been in Nashville Sunday, wheelchair-bound with fellow Cincinnati Reds alumni, reeling in the years, but he’d had two heart procedures in the past five years.

His public obsolescence became the saddest part, because Rose’s contemporaries remember someone vastly different.

Rose popped onto the scene in 1963. He had a crew cut and a sense of mischief and no discernible fear. When he drew a walk in an exhibition game and ran down the first base line, Whitey Ford of the Yankees ridiculed him as “Charlie Hustle,” not dreaming he had coined a lifetime nickname. Rose was also brash enough to hang out with Frank Robinson and Vada Pinson, Cincinnati’s Black stars, because the veterans resented him for unseating second baseman Don Blasingame, and because, as he said, “those colored guys treat me like a human being.”

Rose hit .273 and was the Rookie of the Year. As the 60s progressed, he kept his buzz cut “because they have barbers in Cincinnati,” although he adopted the Prince Valiant look soon enough. And as the Reds made trades to build their fearsome Big Red Machine of the 70s, Rose was more than willing to switch positions. He played second base, third base and all three outfield spots, and in Philadelphia he tried first base, at the age of 38, and handled that too. He didn’t worry about how it would affect his hitting, because nothing on earth could do that. One day in Wrigley Field, Rose had a savage batting practice session, zapping line drives all over. He emerged from the cage, saw a couple of writers standing there and said, “Let me tell you something. I can fucking hit!”

Yes, he could. He had a league-leading .418 on-base percentage in 1979, that first year in Philly. When he was 41 he played every game, had 720 plate appearances and struck out 32 times. His stated goal was to get 200 hits, score 100 runs and hit .300, and he did those things 10, 10 and 15 times each, and he did them all in the same year six times. He also led the National League in doubles six times.

To do that he had to ignore a lot of aches and pains, although he was built like an oblong granite slab and seemed impossible to hurt. He played at least 162 games seven different times.

And, of course, he wound up with 4,256 hits. Is that a record made to be broken? Not in the foreseeable future. Only four active players have 2,000 or more hits, with Freddie Freeman the leader at 2,267. He and Jose Altuve are 34, Andrew McCutchen 37 and Paul Goldschmidt 36.

Rose loved his numbers and knew them at all times. Did that make him selfish? Not really. As he said, “I want to go 3-for-4 every game. If we all did that, we’d win all our games.” He was the first to take the rookies out for drinks on the road, even though he didn’t drink. His project in Philadelphia was to convince Mike Schmidt he could be as good as everyone but Schmidt thought he was, if only he played the game the same way every day. And Rose never quit promoting the game. It didn’t matter if you were from the Wall Street Journal or the Lubbock Avalanche-Journal, Pete would talk baseball with you until it was time for him to do something important, like hit or make a bet. He noticed a young Phillies’ pitcher decided to imitate Steve Carlton one week, refusing to speak to reporters. “Why the hell would he do that?” Rose asked. “Doesn’t he want to make any money?”

It figured that Rose was even better when more people were watching. In 67 postseason games he had 86 hits, for a .322 average, and he even hit five home runs. Overall he hit .312 with men in scoring position, as opposed to .303 overall. In League Championship Series games, the springboard to the World Series, Rose hit .381 with a .964 OPS.

Through those years, as the Reds won two World Series and Rose won an MVP award, he was probably the most charismatic player in the game, the first offensive player who didn’t rely on power to make a million dollars a year. He was as sure of his identity as anyone in baseball, maybe ever. The sluggers might strike out, the ace pitcher might get lit up, and even Rose might go 0-for-4, but the percentages were high that Rose would also do something characteristic and dynamic. He could guarantee the patron that he would always be Pete Rose.

And if the whole world had been confined to the area inside the white lines, Rose might have lived a carefree, distinguished life. (When he played tennis he made a habit of clipping the lines and then saying, “That’s what it’s there for, ain’t it?”) But when he left the ballpark and ventured into the everyday streets, he really needed a passport.

Pete’s lust for hitting a baseball was equaled only by his sexual desires, and the late-night bars were full of stories about the times his girlfriend would bump into his wife, especially a tale involving the flushing of birth control pills down a hotel toilet in Atlanta. The day his first wife Karolyn filed for divorce, Rose was in the visiting clubhouse in Shea Stadium. His reaction was, “What time are we hitting?” That never rang entirely true, primarily because Rose always knew what time he was hitting. But it wasn’t a misrepresentation.

The betting was an even more troublesome addiction because it brought in some dicey characters who knew how to supply Rose’s desires. It wasn’t just baseball. Rose kept up with everything and made little effort to disguise it. When he was betting on the Reds while he also was managing them, he failed to see the inherent wrongdoing, that if the day ever came when he didn’t bet on the Reds, alarms would go off. But that was the dichotomy. The only rules he felt like observing were at the ballpark. The ones that were codified by baseball, or by marriage vows, were just words.

The only time Rose let his defiant mask slip was when he talked about his extended family, or families, and how he hoped that they could see him inducted into the Hall or welcomed back into baseball. (Fox Sports did use him in the postseason studio at times, and that had to be approved by MLB.) He was indignant that Pete Jr. never got a chance at the big leagues. “He had 2,000 minor-league hits,” Pete Sr. said, although the figure was 1,879 in the minors, independent and international leagues. Junior did get 16 plate appearances with the Reds in 1997, but he spent more time in major league clubhouses than some veterans did, hanging with Eduardo Perez and Ken Griffey Jr. while their dads were being legendary.

The baseball Hall needs Rose the way the country music Hall needs George Jones or the chess Hall needs Bobby Fischer. It’s not the Hall of Well-Adjusted People. It should be the place where players of impact are recognized. There is no question that baseball was a brighter, richer place because Rose was at its core, or that people who didn’t know a slider from a playground slide knew who Rose was, and that if we all loved what we did the same way Rose loved the game, our national GDP would be unmeasurable.

The Cincinnati Enquirer sent a reporter to Rose’s statue outside the Reds’ ballpark, as fans gathered. Shaun Snyder remembered the relationship with his own father. “My dad and I didn’t like the same music, movies or TV shows,” he said. “I liked the Fresh Prince of Bel Air and hated it. But what we had in common was Charlie Hustle. That’s what everybody had. Me, my father and my grandfather.”

Eventually Rose reduced, or promoted, everybody to the same perfect age. That’s why we chose not to recognize the squinting, fading fellow who sat behind desks in Vegas and signed processions of baseballs without the slightest interest in looking up at the strangers who brought them. Odds are, Rose didn’t recognize him either.

Sensational retrospective.

Brilliant article. Well done.