Senate starts to fix the problems that the colleges won't.

A proposed bill by three Senators, at first glance, will serve the players well.

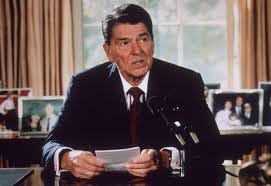

President Reagan once said the nine most terrifying words in America were “I’m from the government, and I’m here to help.”

Actually he said it far more than once, and it was always good for wild applause, anytime between Reagan’s California governor’s race and his retirement from public life in 1989.

It also assumed the basic instincts of all businessmen and business institutions were pure, and therefore needed no oversight.

That’s not a sound assumption, not then and not now, and that’s why the U.S. Senate is here to help. This time the distressed party is the world of college athletics. If there were no problems, hypocrisies, and cesspools to clean up, it wouldn’t have to waste its time worrying about unlimited, anarchic free agency in basketball, or football players who might make millions in NIL contracts and, ten years later, forget their children’s names.

The truth is that college sports has become what everyone demanded it become, except it happened without the increments that could have kept it between the ditches. The changes came suddenly with no regard for consequences. Now it needs to be rolled back, and those rollbacks need to come with the other reforms that had nothing to do with the transfer portal, also known as the Golden Door.

Sen. Cory Booker (D-NJ), Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-Ct) and Sen. Jerry Moran (R-Ks) have introduced the College Athletes Protection & Compensation Act.

On paper, it makes a lot of sense. Since most football games are won on paper these days, particularly the dotted line at the bottom of a player contract, here’s hoping the Senators can slip it underneath the steaming pile of blarney that dominates the Congress that cable news purports to show.

Most of the legislation would deal with the name, image and likeness (NIL) contracts that are triggering massive player movement, and theoretically adding to the imbalance of competition, particularly in college football, although the competition wasn’t exactly balanced before NIL came along.

The bill would create a College Athletics Corporation that will oversee NIL deals, with a board of directors, one-third of which would have to be current athletes or those who played sometime in the previous 10 years.

That board would establish a uniform NIL policy and would carry subpoena power, in hopes that the NIL deals would be to enrich current athletes and not become “collectives” that throw money at incoming recruits.

All the NIL deals would be reported to the CAC within seven days of their inception. Schools would be barred from serving as agents or influencing players to use, or avoid, certain agents, although the CAC will have the power to approve all agents.

More significantly, the legislation will at long last require the schools to cover a player’s medical expenses after he leaves the school.

If a school makes $50 million through its athletic programs, it will pay those medical expenses for four years, and will have to contribute to the fund. Other schools that make fewer dollars will have to float those bills for fewer years, but the point is that the colleges will no longer be permitted to squeeze the life out of their players, particularly in football, and then cast them onto the street.

Better yet, players will be required to take courses in financial literacy. Why all students are not forced to do so is a larger question, but at least this way a player will be forewarned about credit card debt, the subtleties of mortgages, and the implications of taxes. Maybe that means they put off insolvency for six years instead of three. But it might also mean a lot less PRSD (Post Retirement Stress Disorder) for those who never saw their money, much less the drain.

At least it will provide athletes with courses that might improve their lives, and that’s a good thing.

There is no mention of the concept of college players as “employees,” which is still to be litigated, and there is no suggested tweaking of the transfer portal. You can’t really modify mass transfers through legislation because the same kneejerk transferring is a staple of the top high school programs, in all sports. As much as we yearn for the days when players were loyal to the neighborhood school and their teammates, that’s so 20th century. But, again, that’s what we said we wanted, and so the basketball player who shows up at his fourth school in four years will be more commonplace, even though the NCAA says it will crack down on the waivers that a two-time transfer supposedly requires.

Meanwhile, the colleges await the Pac-12’s new media-rights deal, which commissioner George Kliavkoff said is imminent. That, supposedly, will determine whether the Big 12 can successfully go after Colorado and the Arizona schools, or if the Big 10 can work on annexing Oregon and Washington.

The senators’ plan does not specifically address academic performance, so there’s currently nothing to safeguard the Brigham Young soccer team from playing a Big 12 conference game at Central Florida in the middle of the week.

And, of course, this will be the final year of the 4-team College Football Playoff. Next year there will be 12 teams in the fold, more cannon fodder for the Alabamas, Georgias and Ohio States, more blowouts, more teams playing an inhuman number of college games, and, of course, more TV.

This bill hasn’t been formally introduced and is no lock to pass, at least not anytime soon, with the Senate essentially working 3-day weeks. But it is an example of the things that happen behind the scenes in Congress every day, the little victories that Democrats and Republicans collaborate on, certainly not the stuff of runaway videos or cable ratings, but things that make American lives just a little better.

An example: Thanks to collaboration led by Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY) and Sen. Joni Ernst (R-Iowa) and backed by a majority of Senate Republicans, sexual assault in the military is now handled by independent prosecutors, not unit commanders.

The government inspects our food, lands our airplanes, fixes our bridges and provides school lunches which, in some parts of the richest country in the history of the world, are the only meals kids get all day.

But no one who watches the ersatz news from the dinner hour until midnight will learn anything about the grunt work that men and women of good faith sometimes do in the Capitol.

Let’s be clear. No one is pretending that a course collection of college sports is anything but a First World Problem. If one really wanted a system that put sports in its proper context, the athletic scholarship itself would be a goner. That’s not going to happen, so we have to bring our excesses to heel, to sand off the edges of a bloated, ridiculously expensive industry. In this case, it means treating players a little more like human beings.

One doubts President Reagan, the Gipper, would have opposed this bill or any others that make college athletics conform to logic.

Besides, in Reagan’s eight years, there were 230,000 workers added to the federal bureaucracy. Somehow they didn’t terrify us at all.