Some coaches built programs. Lefty Driesell invented them.

Talent, wins and nonstop excitement followed the Lefthander, who passed Saturday at 92.

In 1968 and 1969, UCLA won NCAA men’s basketball championships. Maryland won 16 games total, six in ACC competition.

Maryland hired a new coach, Lefty Driesell, from Davidson, where he had grown a Top 10 hoop program out of rocks and rubbish. When Lefty got to the press conference, he did not talk of winning seasons or maybe an NIT bid. He said his hope was to make Maryland “the UCLA of the East.”

This would have been widely mocked had it been taken seriously at all. Driesell, with his southside Virginia accent and his knack for mangling the language (“I haven’t looked at the ta-tistics”), was obviously in Barnum mode. Maryland had as much business equating itself with UCLA as Dean Phillips does running for President. Cole Field House was empty, the ACC was under the thumb of North Carolina and South Carolina and North Carolina State, and Driesell could have stayed at Davidson forever. This was a leap of the blindest faith.

And, no, Maryland never became the UCLA of the East, which is a hard concept to remember now that UCLA isn’t even the Gonzaga of the West. Driesell never reached a Final Four.

Funny, how nobody remembered that on Saturday, when the Lefthander died at age 92, his niches secure: a Hall of Fame member, one of the most influential coaches in college hoop history, and a character who brought out every reaction but neutrality..

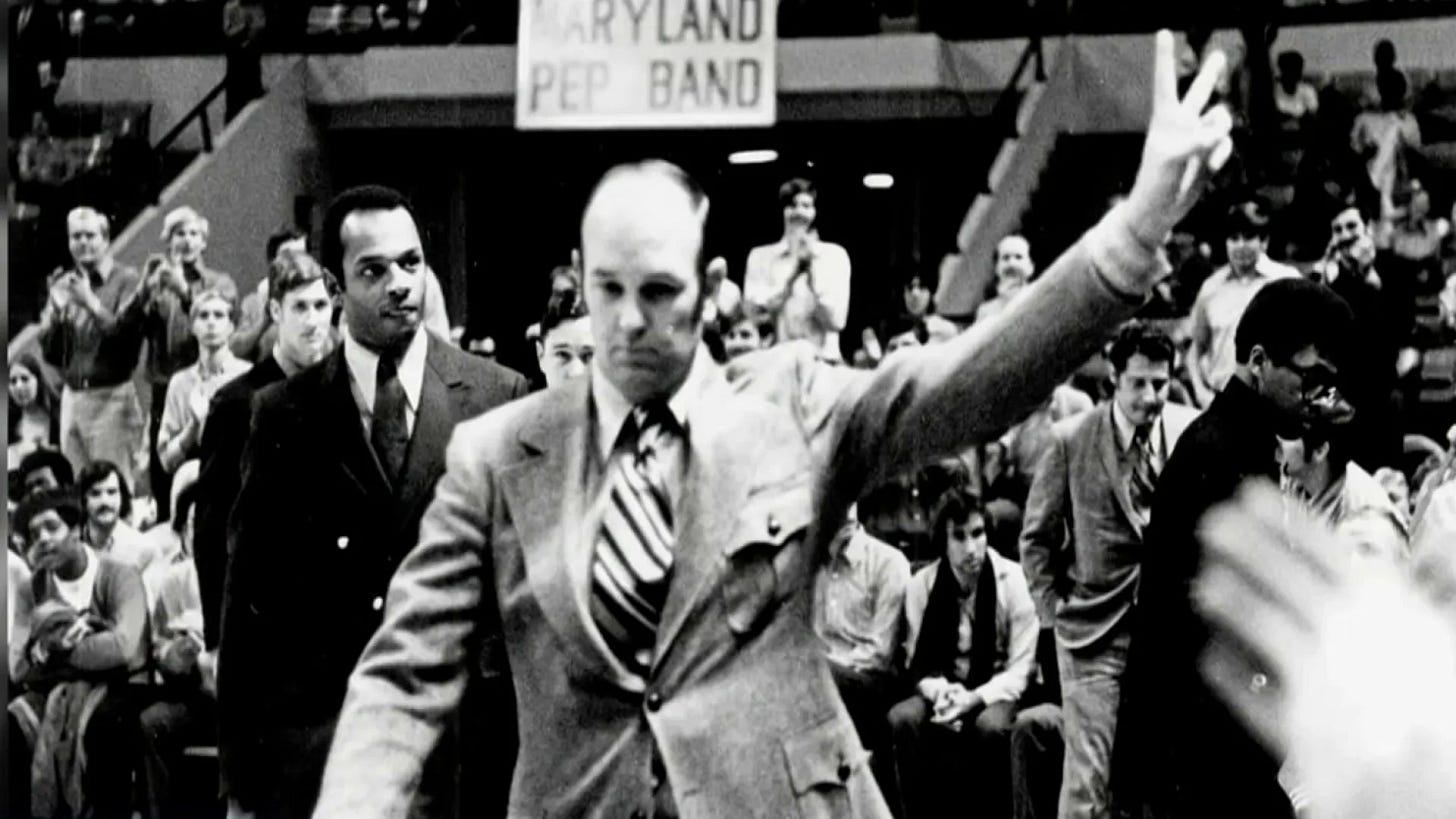

The Terrapins not only filled Cole, they packed every building in the conference, and fans saved their jeers and cheers for the moment Lefty walked to the bench. He was a big, balding man who lumbered around like he owned the place, and at home the band played Hail To The Chief when he emerged, and he flashed the V sign, sometimes two of them, the same way Nixon did. After Maryland’s wins the band would play “Amen,” by the Impressions.

He captured Washington and Baltimore fans like no college coach in the area ever has, and his teams played a lot higher than their results. He had a Don Quixote way of running into windmill blades, but in the end he was revered as a players’ coach and a man who lived for the fight and the attention.

Parenthetically, he might have been the best recruiter in the history of the game, considering the players he signed and the people he outworked to sign them.

How about this team? Moses Malone and Tom McMillen up front. Len Bias and Albert King attacking from the wing. Buck Williams and Len Elmore rebounding and defending. John Lucas rushing the ball upcourt and making flat-footed, left-handed shots while Brad Davis and Maurice Howard fill in the blanks in Driesell’s 3-guard offense, a new look that gave Maryland a clean sweep of Tobacco Road in 1975 – wins at North Carolina, N.C. State, Duke and Wake Forest.

Malone, of course, signed with the ABA after Maryland signed him from Petersburg, Va. That one hurt. The other one that hurt was Charlie Scott, who, the legend goes, was all set to sign with Davidson until the day he walked into a local diner and was denied service because he was Black. Scott went to North Carolina and hit what would have been a 3-pointer today to beat Davidson in the ‘69 East Regional Final, for the second consecutive year. That was the game to go to the Final Four, and it was in Cole Field House, the site of Lefty’s next game and the forthcoming saga.

McMillen, who became a Rhodes scholar like Danny Carroll did when Lefty was at Davidson,, was just as famous a recruit as Malone was. He was locked up for North Carolina until Driesell somehow persuaded the family otherwise. Elmore was a Harvard Law graduate. Lucas, who could have played pro tennis, was an ebullient floor leader and Lefty’s feisty soulmate. Lefty called Williams “my horse,” and King was considered the best high school player in his class, ahead of Magic Johnson. Davis was one of seven first-round picks who played for Lefty at Maryland.

Let us not forget Fred Hetzel, Mike Maloy and Dick Snyder, Driesell’s stars at Davidson, a school that had 11 consecutive losing seasons before Lefty got there. Driesell coached the Wildcats into the NCAA tournament four times.

Driesell’s recruiting knack was very simple. Establish a connection, especially with Mom, and knock on the same door as often as possible. He was a legendary encyclopedia salesman while he was still a high school coach in Norfolk, and this was pretty much the same thing. Eventually he recruited too well for his own good, or at least too well for his coaching reputation. Sportswriters gave his players credit for the wins, blamed him for the eventual losses. This rankled Driesell, especially when he was compared unfavorably with Carolina’s Dean Smith. But he wouldn’t apologize for what he did best.

“I hear people talk about this coach and that coach,” Driesell said. “They say, ‘He’s a great coach. If he could only recruit.’ That doesn’t make any sense to me. You gotta have players to win.”

And that was the thing. Maryland’s players usually played hard, generally played together and habitually won. In a five-year span beginning with the 1972 season, Maryland won 119 games and two ACC tournaments. After the 1980 tournament, Lefty promised to weld the trophy to the hood of his car and drive it around North Carolina, honking the horn.

He went to eight NCAA tournaments as the Terps’ coach, but the one that he didn’t attend turned out to be the shape-shifter, the one that turned a private prom into today’s unruly, coast-to-coast Big Dance.

In 1973 and 1974, Maryland was 46-12. Its skills were massive but its timing was lousy. N.C. State, with David Thompson, was going 57-1. The two played the first Super Sunday game in ‘73, preceding the Washington-Miami Super Bowl, and State won at Maryland. They met in the ‘73 ACC tournament final, in the days when only one team per conference could attend the NCAAs, and the same thing happened.

Finally, at the ACC final in ‘74, Maryland thought it could break through. The result was 103-100 in overtime, in favor of the Wolfpack, a game that wasn’t nationally televised but had a mighty impact. The disconsolate Terps turned down an NIT invitation, but the NCAA, recognizing what Maryland had done and what USC had done in several futile Pac-8 challenges to UCLA, opened up the tournament to 32 teams and five conference runners-up (including Maryland) in 1975.

Coincidentally, John Wooden retired after UCLA won the ‘75 final. It has won only once in the 49 years since. With more and more competent teams invading the 68-team mix, the tournament has become outrageously unpredictable, and the bracket itself has become a national hobby. Maryland is why that happened. N.C. State went on to jolt UCLA in that ‘74 Final, and Maryland could have easily done the same.

It ended for Driesell when Bias, just after he was drafted second overall by the Celtics in the ‘86 draft, died of a cocaine overdose. An allegation that Driesell interfered with the investigation was proven false, and he was cleared, but Maryland officials parlayed this incident with some academic neglect in the program – two Rhodes scholars notwithstanding – and Driesell was forced out. Mike Krzyzewski later said that Driesell would have broken the alltime wins record if he hadn’t been “scapegoated.”

That wasn’t the end for Driesell, who spent nine years at James Madison and Georgia State and got to NCAA tournaments with both. He wound up with 782 Ws and a .666 win percentage.

But Driesell’s transparent emotion, his ambition and verve, will extend beyond that.

It was the way he would go into Cameron Indoor Stadium, where a fan would have a picture of Lefty’s forehead, bearing a gas gauge stuck on “E.” Lefty would usually win and then say, “I must not be too dumb. I went to Duke.”

It was the way he protested some calls by referee Hank Nichols, who told him later that the tape showed Nichols had gotten them all right. “You mighta gotten ‘em right on tape,” Lefty said, “but you missed ‘em in the damn game.”

It was the way he would go to the ACC meetings at Myrtle Beach and walk around the outdoor balconies with firecrackers, looking to light them and shove them under doors, like a freshman on spring break.

And there was the time Maryland was practicing at North Carolina, the day before McMillen’s first game there, a hypertense occasion that wound up favoring Carolina. A reporter from the Daily Tar Heel went up to Lefty and introduced himself and his affiliation.

Driesell was aghast. “You a Daily Tar Heel?” he cried. “Damn. I feel sorry for you. You got to be a Tar Heel every day. These players, they just got to be Tar Heels twice a day. But you got to be one every day!”

Eventually Driesell got the best possible revenge on the begrudgers and hecklers by outliving them. All he had to do was be Lefty, every day.

Great anecdote. Fabulous insight.

Awesome piece. That State-Terps game here in Greensboro is the subject of recall every year. Lefty was an amazing recruiter. We thought McMillen was going to Kentucky.