College football season did not always last from 12:01 a.m. on January 1 to midnight on Dec. 31.

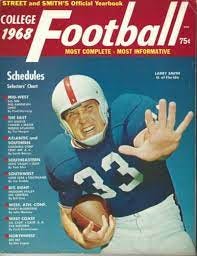

There once was a clearly defined Opening Day. It was the day that Street & Smith’s Football Yearbook landed in the magazine rack at the local drug store, or showed up at the newsstand, back in the days when news could stand on its own.

That was usually in late July or early August. No need to rush. The seasons were 10 games long and did not begin until the middle of September. In the back of the book, there was a scheduling grid, with each team’s season set in a box, with symbols indicating whether it was a night game, what last year’s score was, and who should be favored. Cleverly the publishers left enough room for you to write the eventual score. That was the extent of the analytics.

There are far more football magazines now. There is a very good one, Athlon’s, that is faithful to Street & Smith’s function, which is to lay out the names of the players on each team and their realistic hopes for the season. Athlon’s information is far more extensive than its predecessor’s, but it is designed for the honest football fan, the one who watches for football’s sake.

Unfortunately, Athlon’s can be buried in a truly sobering wall of magazines that are devoted to the colder parts of the game. Most of the mags are servicing those who play in fantasy leagues. Almost all are designed for the bettor.

Phil Steele puts out a popular, gigantic yearbook that lures the reader into numerical quicksand, as deep as that person wants to go. If USC’s performance against the spread over the past five years is something that might change your financial future, it’s all here. A publication called Pick Six also goes under the hood to find the statistical wiring.

And if you need to know how each player is “graded,” subscribe to Pro Football Weekly.

Street & Smith’s wasn’t plugged into the Information Age. Its team summaries rarely had quotes from anyone. They laid out the probable starting lineups and position battles. They were grouped by region, back when college football respected geographical proximity. Arizona State was in the Western Athletic Conference. The Southwest Conference had seven teams from Texas, plus Arkansas. The Big 8 and Big 10 were numerically correct.

There was one and only one cover boy. Dick Butkus of Illinois won the honor in 1964. The stories weren’t particularly hard to write because the rosters were so resistant to change. Freshmen weren’t eligible yet, so no one bothered to write about recruiting. Transferring was heresy. It really mattered when a team returned 15 or so starters.

Sure, all games change, but college football in 2022 might be the least recognizable to those who were dropped in from mid-60s. For instance, Tom Siler’s Street & Smith’s profile of LSU contained this: “Remi Prudhomme, 236 (pounds), could be the big man of the LSU defense.” Since then LSU has had at least one quarterback who surpassed 236.

Paul Zimmerman of the L.A. Times summed up the West, and not just the Pac-8. He wrote profiles of Santa Clara, Santa Barbara, San Francisco, Riverside, LaVerne. In his profile of USC he said there “are no prolblems at left halfback as long as Mike Garrett is healthy” and pointed out that Garrett “is a great defensive player” as well. That’s right. There were a lot of Ohtani types in college football, players who went both ways, because there was limited substitution between 1954 and 1964.

Zimmerman also pointed out the USC center, the 210-pound Hudson Houck, who later turned much bigger men into much richer men as the line coach for the Rams and Cowboys.

And in the photo gallery of the Southeastern Conference, you could see Joe Namath pitching out. The caption: “Joe is bidding for pro recognition.” His bid was successful.

The words weren’t as memorable in Street & Smith’s as the photos. Most of them were single shots of players carrying the ball and trying to look fierce. The main photographer was Jim Laughead, who toured the country in a station wagon with his son-in-law and snapped those “action shots” of 74 college teams. His specialty was the “death dive,” in which he set the camera low and told the player, usually a lineman, to hold his hands over his head, work up a violent growl, and then jump and land on his chest. It appeared the actor was jumping out of an airplane, but it was fairly harmless, at least until one death-diver fell on a football and turned Kansas State-purple.

This was back when men were men and phones were phones. But an enterprising player might want to recreate the Death Dive today, in black-and-white, to satisfy everyone’s retro edge. Could be big NIL bucks.

No one should get too nostalgic about the game back then. For one thing, 1964 was when the Civil Rights Bill was passed, and the football aftereffects were far away. On the cover of the ‘64 magazine, a headline read, “Dixie Starts Integrating,” as some ACC teams welcomed Black players. One can imagine some fans took the headline as a warning instead of a celebration.

And even though Street and Smith’s faithfully wrote something about the Oberlins, Occidentals and Sul Ross States, you didn’t find a word about the Gramblings, Prairie Views and Jackson States that would eventually stock the All-Star teams of the American Football League.

As Southern Blacks like Bobby Bell, George Webster and Charlie Sanders flocked to the Big 10, and as Pac-8 schools rubbed out the color line, it became harder to pretend. Between 1950 and 1970, SEC teams won five national championships, as determined by the votes of writers and coaches. Big 10 teams won seven, and Minnesota’s Sandy Stephens became the first Black QB to do so.

In 1981 Clemson won the championship with Homer Jordan, a Black quarterback. In 1990 Georgia Tech and Colorado won the two versions of the title with quarterbacks Joe Hamilton and Darian Hagan.

All along, SEC schools were tightening their recruiting hold on Black players from the Deep South. Beginning in 2006, a Southern-based team — either an SEC member, Clemson or Florida State — has won at least one of the two versions of the title every year but one.

The Big Ten has won two only national titles since Michigan split the 1998 crown with Nebraska. Both belong to Ohio State.

Street & Smith’s was hardly alone in its ignorance of what was happening. The HBCUs had no chance of commanding one of the Saturday afternoon TV slots, but then hardly anyone else did, besides the powerhouses. The reason the Rose Bowl was such a resonating TV event was that it was the only time all year that America saw the stadium, or the Pac-8 champ itself. When you never saw the players live or in living color, Street & Smith’s ebony/ivory photos were the only windows to their world.

There was one claim Street & Smith’s made that was inarguable. It was “most complete and most informative,” in its day. Plus, you got all that for 50 cents. Perhaps we failed to sense the gathering storm of societal fragmentation when we got the 1968 edition, and it was 75 cents. But all we saw was the first falling leaf of a new season.

(30

)

Fantastic, Mark. With all the tweaks and changes, from mythical titles picked by pollsters to the CFP, there’s been one constant. Major college football is closed club, run by a handful of school presidents dealing face cards to its frenemies.

Great trip down memory lane!!