Study the understudies in this World Series

Over the years with the Yankees and Dodgers, the wingmen have had their moments.

As television dawned, the Yankees and Dodgers seemed like cast members in a regularly-scheduled drama. They were World Series opponents in ‘52, ‘53, ‘55 and ‘56. They also played in ‘41, ‘47 and ‘49. They played back to back in ‘77 and ‘78. They get together for the 12th time on Friday night in Dodger Stadium, both of them with fatted-calf rosters but an undeniable hunger. The Yankees haven’t played in (or won) a Series in 15 years; the Dodgers haven’t won a full-season Series since ‘88. Some will say it’s like Kim Jong Un against Putin; some will say it’s like telemarketers against IRS agents. What’s a fan to do? Watch, is what they’ll do. Despite the assumed villainy, this Series has a chance to actually be heard, unlike all the ones that were suffocated by NFL pillows.

Aaron Judge, Shohei Ohtani, Juan Soto, Mookie Betts, Freddie Freeman, Giancarlo Stanton….it’s like an Ocean’s 11 cast of big boppers. And, yes, the stars have often come out in these Series. Sandy Koufax was hardly ever better than he was in 1963, and Reggie Jackson went extra-terrestrial when he hit those three homers in Game 6, 1977. Yogi Berra played in 14 World Series, won 10 and had an .811 OPS overall, but he was particularly tough on Brooklyn, with 19 RBI in 27 games over four Series in the 50s, and a .400 batting average in ‘53 through ‘56.

But, just as often, the mystery guests have taken over the stage in these Series, and in some cases their work for the Yankees or Dodgers has become their identity. Tommy Edman honored that tradition when he won the NLCS Most Valuable Player Award for the Dodgers. Keep an eye on Jon Berti or maybe Miguel Rojas. Someone will honor the tradition of the following grunts of October:

BILL SKOWRON

Moose was actually a Yankee star in the 50s and early 60s, a big righthand bat to clean up what Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris left behind. But the Yankees traded him to the Dodgers for pitcher Stan Williams before the ‘63 season, and they looked smart in doing it. Skowron scuffled in L.A., hitting .203 in 89 games with just four homers. The Yankees replaced him with Joe Pepitone, a prospect who had lusted for Skowron’s job. After the trade, he sent Skowron a telegram: “Dear Moose: Told You So. Joe Pep.”

Still, Walter Alston had a way of sensing things. Seven years prior, Skowron had grand-slammed Preacher Roe in Game 7 of the Series. Alston knew how many Octobers Skowron had decorated, so he installed Skowron at first base against the Yankees. In Game 1 Skowron drove in the first run for Koufax, then drove in another just for fun. In Game 2 he homered in another win. The Dodgers swept the Series and Skowron hit .385.

“Hell, I wanted to come back and beat the club that traded me,” Skowron said. “I didn’t expect to play in this thing until I read the lineup in the paper. I know I’ve been a donkey. But this tastes awful sweet.”

And Pepitone? Game 4 was tied, 1-1, when Jim Gilliam hit a bouncer to Clete Boyer at third base. He threw to first, but Pepitone lost the ball in the crowd and the ball hit him in the arm and rolled down the rightfield line. Willie Davis came through with a sacrifice fly and that’s all Koufax needed. Someone at Western Union must have smiled.

MICKEY OWEN

In 1941 Owen was an established National League catcher. He set a N.L. catchers’ record for most consecutive chances without an error. The Yankees won the first two games of the Series and Brooklyn, in its first Series since 1920, won the third and had a 4-3 lead with two outs and nobody on in the ninth.

The batter was Tommy Henrich. On a 3-and-2 pitch Hugh Casey sent a hard-breaking curve to the plate and Henrich missed it. Fans began to rush onto the Ebbets Field grass, but then they realized that Owen hadn’t caught the ball. Henrich ran to first. Ask Steve Bartman what happens when you open a playoff door.

The Yankees went single-double-walk-double and scored four in the ninth. They won, 7-4, won the next day and won the Series in five.

“Owen’s crime did not end the ballgame,” wrote John Lardner, “but every Yankee blow thereafter was like the blow of a club on the head of an unconscious man.”

“I bet he feels like a nickel’s worth of dog meat,” Henrich said.

The play did not sour Owen’s career. In 1942 he finished fourth in MVP voting. It was the second of four consecutive All-Star Games for Owen, who played 13 years in the majors. After baseball he was the sheriff of Greene County, Mo., for 13 years and ran for lieutenant governor in 1982, finishing third.

But he knew what the first paragraph of his obit would look like. He never offered an alibi for the play and, in fact, said he would have been “completely forgotten” without the hiccup. Besides, not everybody criticized him.

“I got about 4,000 wires and letters,” he said later. “I had offers of jobs and proposals of marriage. Some girls sent their pictures in bathing suits. My wife tore them up.”

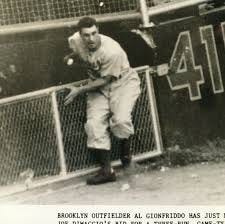

AL GIONFRIDDO

Gionfriddo was a 5-foot-6 outfielder who played four years in MLB and only played 37 games for the Dodgers. In 1947, during the first televised World Series, he went to leftfield as a defensive replacement in Game 6, with the Dodgers leading 8-5. Joe DiMaggio appeared to have fixed that with a drive to left, and two Yankee baserunners began running. Gionfriddo scampered back and somehow caught it. If you’ve seen that newsreel footage of DiMaggio kicking the ground as he neared second base, that was the play. Broadcaster Red Barber said it was the only time DiMaggio ever let emotion seep out.

The Dodgers won, 8-6, but it’s not like Gionfriddo actually robbed DiMaggio of a homer. He was too far from the fence for that. Still, an extra-base hit would have been fine with the Yankees, too. It was a startling play. It also was the final putout of Gionfriddo’s career.

The Yankees rebounded to win Game 7, 5-2. Joe Page was the “closer” and finished it out. He came to the mound in the fifth. Yes, he was a one-man “bullpen game.”

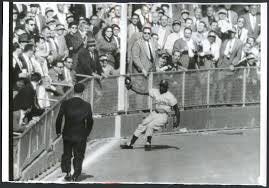

SANDY AMOROS

The day after the Yankees won the 1941 Series with Owen’s help, the Brooklyn Eagle headline blared, “Wait Till Next Year.” That became an albatross for 14 years. The Dodgers had lost so many Game 7s to the Yankees that it was difficult to walk confidently into Yankee Stadium in 1955. In the sixth inning of Game 7, the Dodgers and Johnny Podres had a 2-0 lead. What could go wrong, you ask? What kind of question is that?

Sure enough the Yankees put two runners on base. Amoros was the defensive replacement, just as Gionfriddo had been in 1947. Berra, the scariest thing any Dodger fan could see in October, sliced a drive down the leftfield line off Podres. Amoros was playing in left-center. Somehow he jetted his way to the edge of the stands, held out his glove and caught it. Then he threw to the infield for a double play.

Podres finished it off. The Dodgers won. Next year was here. And without Amoros, who knows?

Amoros played seven years in the big leagues and was looking forward to returning to Cuba, where he had land and lots of baseball ambitions. Fidel Castro took over the government, and when Amoros declined Castro’s offer to manage a team, the dictator took everything Amoros had. Castro finally let Amoros leave the country a few years later, and the Dodgers arranged for him to get his MLB pension. But alcoholism and illness kept him down, and he died in destitution, at 62.

One followup: The Dodgers celebrated their championship that night at the Bossert Hotel. Vin Scully’s date for the evening was an RCA publicist named Joan Ganz, later to be known as Joan Ganz Cooney, the inventor of Sesame Street. “I think I might have messed that one up,” Scully would say, decades later.

JOHNNY KUCKS

You are forgiven if you think Don Larsen won the World Series when he pitched his perfect game in 1955. That was only Game 5. Clem Labine won Game 6 for the Dodgers. Whitey Ford, the Chairman of the Board, was fully rested for Game 7, but manager Casey Stengel had his thinking cap on. At that time, coach Frankie Crosetti would put a baseball into the shoe of the pitcher who would start the next day. Johnny Kucks looked down and saw the ball in his shoe. “I started to give it to somebody else,” he said.

Kucks wasn’t a wild choice. In his second year he won 18 games for the Yankees. But Stengel only used him twice in relief before Game 7, and not since Game 2. The logic was that Kucks, with his sidearm sinker, could get some ground balls from the Dodger sluggers. It worked, but a lot of things work when the bats are booming. Kucks and the Yankees won, 9-0.

Kucks got 16 ground balls that day, including eight from the Dodgers’ first eight batters. But when Pee Wee Reese and Duke Snider reached base with one out in the first, Kucks noticed Ford and Tom Sturdivant warming up. He got Jackie Robinson on a double play to end that. Later, Robinson was Kucks’ only strikeout victim of the day. It was the last game Robinson would play in the big leagues. Kucks was around for only four more years, two of those with Kansas City, a franchise the Yankees used as a recycle bin. He did not have another winning season.

Obviously Larsen was the one who penned history in that Series, but Kucks wasn’t totally unnoticed. “He got a car,” Kucks said later. “I got a fishing rod.”

BRIAN DOYLE

The kid from Horse Cave, Ky. did not have the World Series in mind when the 1978 season wound down. But when Willie Randolph had knee problems in September, Doyle and Fred Stanley split time at second base. It was Doyle’s first year in the big leagues, and he hit .192. He played three more years, and that was still his career high. His brother Denny broke into the Phillies’ lineup alongside shortstop Larry Bowa and was far more renowned, and Brian had a twin brother Blake who played in the Baltimore organization. What Brian could do was field and throw, and that kept him in position to become a Yankee personage.

With the Series tied 2-2, Doyle got three hits in a 12-2 Game Six win. Shortstop Bucky Dent, hitting one slot below Doyle, also got three hits. Game 6 was at Dodger Stadium, with Don Sutton pitching, and the Yankees were leading 3-2 in the sixth when Doyle got a two-out RBI single. That finished Sutton, and the Yankees opened a 5-2 lead. They won, 7-2, as Jackson homered off Bob Welch, his nemesis earlier in the Series.

Doyle was 7-for-16, a .438 hitter against the Dodgers. Asked what he would be doing if Randolph hadn’t gotten hurt, he said he’d be selling clothes at a store in Bowling Green, near home, because that’s what he did during the off-season. The spree was powerful but not portentous. He was gone at 27 after one year at Oakland, in 1981.

But then he, Blake and Denny opened a baseball school in Kentucky and also helped popularize the scouting showcase. No doubt the Doyles have taught the kids that a day or a week or a Series is out there waiting for someone, even if it means enlistment into Empires of Evil.

Fabulous stuff. Love that Brian Doyle ending. We aren’t related, though both from Kentucky. He should’ve been MVP of that Series.

What a wonderfully written article. Thank you for the backstories that only enhances the aura around this great rivalry and this current series.