The Judge/Bonds comparisons don't need a jury

The sluggers did what they did in different eras, but 62 doesn't equal 73

Maybe this teacher shortage is getting serious. People can’t seem to decide whether 62 exceeds 73.

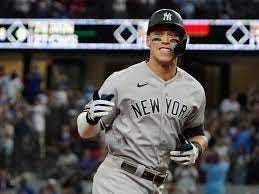

Long before Aaron Judge crushed Jesus Tinoco’s third pitch of Tuesday’s game at Texas, the baseball intelligentsia was debating whether Judge’s 62 home runs surpassed Barry Bonds’ 73 in 2001, along with everything Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa did in between.

Should Judge somehow be designated as the Real Home Run recordholder? Should Bonds’ home run balls suddenly be fished out of McCovey Cove and given forensic testing?

Or should Tom Brady forfeit all his Super Bowl trophies because of Bill Belichick’s candid camera and his resourcefulness with a bicycle pump?

They’re referring, of course, to Bonds finding better living through chemistry, even though there were no real PED policies in baseball back then. The suspicion is that everybody was on something, and probably several things, when you consider the widely winked-at amphetamine habit.

Bonds hit 73 home runs, walked 177 times, hit .328 and had an OPS of 1.379. He had nine more home runs than Sosa. Luis Gonzalez (57) and Alex Rodriguez (52) were the only other sluggers over 50. Bonds’ OPS-plus, a figure that is similar to strokes-gained in golf because it measures the strength of field, was an outrageous 259.

Let’s look closer. Because of all the walks, Bonds only had 476 at-bats. Shawn Green had 619. Bonds had one homer per every 6 ½ at-bats (Sosa was second, with one per nine). Sixty-nine percent of Bonds’ hits went for extra bases. And nearly 30 percent of Bonds’ fly balls were home runs. Remember, PEDs were supposed to be an epidemic that ensnared the pitchers, too. It would be known as one of the great offensive years in the history of the game except for the ones that immediately followed.

Dusty Baker was Bonds’ manager in San Francisco. “I don’t care what they say,” Baker said. “If they want to put an asterisk by it, them 73 that went over the fence didn’t have any asterisks by them.”

That, of course, is the unknowable variable. How many of those home runs would not have been home runs had Bonds been playing straightforward baseball? And if there had been drug testing then, and if everybody was being careful as they seem to be today (we can have the Adderall discussion at another time), would Bonds have maintained the same gap over everyone else? He had already won three Most Valuable Player awards before he bulked up and lost his base-stealing and defensive superiority when he did. He traded them for offensive numbers that we’ll likely never see again. It’s a shame we refuse to look at them now.

It’s also a shame that we can’t seem to appreciate Judge’s season without comparing it to someone else’s, compiled at a different time. His 62 homers were 16 more than anyone else, and only four players hit 40. His 133 runs were 16 more than anyone else, and only 10 players had 100. He won the slugging title by .073 and the OPS title by .992. His OPS was 1.111. Only Yordan Alvarez and Paul Goldschmidt were over .900.

Judge’s season compares favorably with Bonds when you consider the pitching atmosphere. The overall WHIP (walks and hits per innings pitched) in the American League this season was 1.253, and the cumulative batting average was .242. Both figures were the lowest in 50 years. The OPS of .701 was the lowest for a full season since 1976.

The 2001 season was different in Bonds’ National League, where the batting average was .261, the OPS was .756 and the WHIP was 1.382.

In Bonds’ day, pitchers weren’t yet concentrating on spin rates, and pitching coaches weren’t using data to find which pitches worked best. Not everyone roared out of the bullpen with a 98 mph stun gun attached to his shoulder, either. Judge had to deal with an previously unseen level of pitching sophistication.

But then Rogers Hornsby never had to hit a slider, and Grover Cleveland Alexander never had to retire a Black hitter. You can only be defined by the time in which you played.

(Incidentally, it seems that the long games-played streaks have disappeared since amphetamine testing came along. Only Matt Olson and Dansby Swanson of the Braves played all 162. Only nine players showed up for 160. Ten years ago, fifteen did.)

In truth this should be a drama-free celebration, and a retort to those who wonder what happened to baseball and its moments. But your math teacher only cares that Aaron Judge hit 62 home runs under extraordinary circumstances and that, in 2001, Barry Bonds hit 73 the same way. One number is 12.3 percent larger than the other. It’s about stars, not asterisks.

The real argument of substance in this well-written piece hue difficult hitting is today, in the era of very hard throwers and many pitching changes and the incredible varieties of pitches.