The Prince of Princeton

He grew up in Bethlehem, Pa.,, where the gigantic, rusted-out shell of what used to be the steel company continues to stand. His dad worked inside those walls. All around it, you can see the reminders of what happens, and what doesn’t happen, when an American dream rises and walks away. That’s why the dad always told the son that the smart always take from the strong.

That was the title of Pete Carril’s autobiography and the theme of every basketball game he ever coached. The secret, of course, is to be smart and strong, or at least smart enough to be stronger than you look.

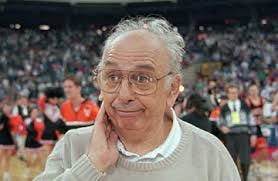

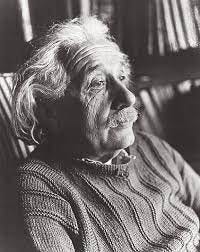

That was the story of Princeton basketball for 29 years, with 13 Ivy League championships and two nights in which the Tigers looked like the smartest insurrectionists in NCAA tournament history. Carril died on Monday at age 92, a little guy who smoked cigars and wore whatever happened to be clean and available. At the end of a typical two-point win, Carril’s hair would be rioting and he looked as eccentric as Albert Einstein, who delivered famous lectures at Princeton. He was far removed, economically and temperamentally, from the Princeton ideal, yet, by the end, the fans thought he’d been born in the other Bethlehem.

“We haven’t had too many characters,” Carril said in 1996, after he had announced his retirement by writing it down on a postgame chalkboard, as his players celebrated an Ivy League championship. “Besides, I’m the character.”

His next game was in the first round of the NCAA tournament, against defending champion UCLA, whose coach, Jim Harrick, had spent much of the week fuming over the fact that the Bruins had to travel to Indianapolis. What about Princeton? “It’s hard to prepare,” Harrick said. “They aren’t on TV very much.”

Those were the days when you scouted through VCR cassettes. There was little UCLA could do against a Princeton offense that became eponymous. Carril spread his team out, had center Steve Goodrich come outside and deliver the ball, and had his guys fake one way and cut to the basket, the classic backdoor. They ran it and ran it, and guarded and rebounded, and as the Bruins became paralyzed by dread, Goodrich found Gabe Lewullis, who had just gotten into the lineup the previous week.

Lewullis ran the back door and Goodrich ignored him. So did UCLA. Lewullis ran another back door and Goodrich put the ball in his hands on a dining hall tray, with silverware. Lewullis scored, Toby Bailey missed on the other end. Princeton won, 43-41, and Carril’s blackboard became as famous as Einstein’s.

“If this had been on a playground, we would have won,” Bailey said.

“You pass, shoot and dribble,” Carril explained. “The greatest players have always been able to do that.”

But the Tigers didn’t screen, at least not often. Carril believed that it just attracted defensive clutter, an extra pair of troublesome hands. He also believed that the Princeton offense, or passing game, or motion offense, would succeed in the NBA. The New Jersey Nets got to two NBA Finals, in 2003 and 2004, with those principles, and Carril became an assistant coach with Sacramento, which pushed the Shaq-Kobe Lakers to overtime in Game 7 of the Western Finals.

Six years before that, Princeton took Alonzo Mourning and Georgetown into the same wilderness, in another NCAA game. The Tigers lost, 50-49. Asked if he thought Bob Scrabis had been fouled at the end by Dikembe Mutombo, Carril said, “I’ll take that up with the Lord when I get there.”

That was when you realized why John Thompson, the Georgetown coach, had steered his son John III to Princeton even though the Tigers gave no athletic scholarships. “I wanted him to play for Pete,” Big John said.

When Carril recruited Craig Robinson, who would later coach Princeton and whose sister Michelle could later be found at the White House for eight years, he told Robinson everything he was doing was wrong. Robinson signed anyway.

When Carril recruited Armand Hill he knew Louisville was also in the mix. “Then he told me something that wanted me to play for him,” Hill said. “The truth.”

Carril liked to tick off all the things a team had to do to win, and then point out that losing required no effort at all. He refused to coach the Tigers as if they were the future lawyers and venture capitalists they were, refused to give them an out. He said they belonged on the court with anybody and should play confidently. Miss five shots? Take the sixth, he’d say.

He loved what Princeton stood for and also loved to tweak Penn, his rival, for bending its standards. He won 514 games and once wondered if anyone had ever done that while playing the majority of his games on the road.

They brought Carril back to Jadwin Gym, to inscribe his name on the court and to put a banner with his name in the rafters. “People are going to step all over me when they decide to play here,” Carril harrumphed, “and then they tried to hang me.”

Not really. Five men have tried to follow Carril. All of them either played or coached for him, and two were part of the magic of 1996. Princeton has won the Ivy League only five times in those 25 seasons.

Carril was only 65 when he quit. But he sensed dissonance when he tried to send a message to his team. He said he was making his assistant coaches work too hard.

The thing that always kept him going, he said, was the sight of a player who took his glow everywhere he went. Carril called them “light bulb” players, like Hill and Robinson. “There’s an intangible feeling that a coach and a player can have that you can delight in,” he said.

Somehow there was a dimming. Instead of denying it, he acknowledged it.

There is nothing more rare and refreshing than a major college coach, in one of the two major college sports, insisting on living in the real world. In 1974 Princeton lost a tough one to Carril and someone wanted his reaction. He replied with a shrug. “Nature is indifferent to the plight of man,” he said.

Nature also abhors a vacuum, but somehow it hasn’t filled the one that measures 5-foot-6, untucked, at Princeton.