The true Sportsman of the Year is revealed through time (not Prime)

On one man's impact, and one magazine's demise.

There’s no exaggerating what Sports Illustrated used to mean. It was to sports, and to illustrating and writing, what Rolling Stone was to Dr. Hook.

When the SI writer came to a college town, the college town paper would write stories about him, or her. That person had access and cachet beyond everyone else, including the interview after everybody else’s interview that, seven days later, would tell the rest of the story. Sports Illustrated got behind the scenes. There were no more scenes behind that.

I was not alone in keeping an eye on the mailbox to see when the window to the sports world would arrive. It would sometimes come on Thursday (exultation), mostly on Friday (relief), a very few times on Saturday (stress).

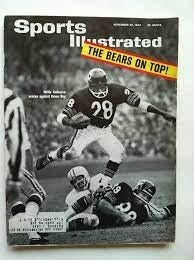

The first issue that came to our house was the Nov. 25, 1963 edition, with Willie Gallimore of the Bears on the cover, jumping over various Packers. Inside was an expose about heatstroke killing various college football players, the booming finances of professional bowling, and a photo essay on the European ski scene. There was the usual contract bridge column from Charles Goren, golf tips from Jack Nicklaus, even a column on dogs and another one on a horse show. There was no ESPN back then to channel our synapses into the revenue sports and, unfortunately, to corrupt Sports Illustrated as well.

Everything I knew about Muhammad Ali came from SI, which covered him obsessively. But the things I didn’t know are the things I remember. People were only dimly aware that black athletes were being compromised, exploited and generally treated like black people everywhere until Jack Olsen’s epic five-part series in 1968. All those years have passed and I still remember a stark profile of Art and Walt Arfons, brothers at odds in the world of land-speed racing, pawns of rivals Goodyear and Firestone. And I remember a profile of Steve Sabol, son of NFL Films pioneer Ed Sabol, when Steve was a fun-loving football player at Colorado College and put a sign in the visiting locker room that read, “Caution. Lungs Can Explode at 7,000 Feet.”

At any rate, the weekly Sports Illustrated was a fine way to spend a solitary afternoon, not because it took that long, but because you wanted to read everything twice. The writers became my models. There was Kim Chapin and Robert F. Jones on auto racing, Dan Jenkins on golf, Curry Kirkpatrick on college hoops and tennis, Peter Carry on the ABA, Pat Putnam and Mark Kram on boxing, Tex Maule on the NFL, John Underwood on college football, William Leggett, Robert Creamer and Jack Mann and, later, Peter Gammons on baseball, Gary Smith and Frank Deford and the unsurpassed Edwin “Bud” Shrake on a multitude of things. And, no, the swimsuit issue wasn’t bad either.

At year’s end Sports Illustrated would present a golden urn to its Sportsman of the Year, or Sportswoman. Billie Jean King was the first woman to get a piece of it. She shared it with John Wooden in 1972, and then Chris Evert won it by herself in 1976. There were some ex post facto embarrassments along the way, like Joe Paterno, Lance Armstrong and the chemical romance SI had with Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa (it wasn’t nearly as excited about Barry Bonds). But generally the award was given appropriately, especially when SI devoted it to athletes doing good out of uniform, when few were watching.

Like the mailbox and the page and maybe the printed word itself, Sports Illustrated has become a threadbare relic over the years. It wasn’t replaced by other magazines, although several have tried. It was extinguished by immediacy, by its own clickbait obsessions, by provincialism (neither Roger Federer, Novak Djokovic or Rafael Nadal ever won Sportsman), and by the breakup of Time/Life itself and the standards therein.

The teardown was complete this month when SI made Deion Sanders its Sportsman of the Year. If you saw that story and figured it came from The Onion, you were not alone.

The excuse was that Sanders had put Colorado football back on national TV, had filled the stadium, and had ruled social media. He was the year’s leading sports figure because he stirred up the most dust. The illogic of this is manifold. For one, putting Deion on the cover to promote newsstand sales would have made sense in the days of newsstands, but not now. For another, SI was celebrating an egomaniacal huckster who ran off dozens of players who didn’t fit his template, with his son’s media company taping every move. In doing so he dislocated lives and relationships. Some refugees said that Sanders never even bothered to learn their names.

You only get away with this if you win. The Buffaloes were 4-8, were humiliated at Oregon and Washington State, and blew a 29-0 halftime lead to Stanford, at home, and lost 46-43 in overtime. Sanders demoted Sean Lewis, the Kent State head coach whom he’d made offensive coordinator, but it didn’t erode Lewis’ marketability. He then got the San Diego State job in about five minutes. Deion also let his son Shadeur, a quarterback with an NFL future, get sacked more than any other QB in major college football.

Another year of this and Sanders will be moving on to his next grandiosity, and the athletic director and president who hired him will disappear into a snowbank. This would be only slightly less absurd as naming George Santos as Time’s Man of the Year.

It also leaves a void. Who was really the top performer of 2023?

Maybe Nikola Jokic, who not only helped Denver win its first NBA championship as a second-round draft pick turned two-time MVP, but proved 7-footers could dominate from the entire half-court.

Maybe A’ja Wilson, whose Las Vegas Aces won a second consecutive WNBA championship as she won Finals MVP, and who has become one of the very few players of any sport to be recognized as the best in high school, college (South Carolina) and pro competition.

Maybe Max Verstappen, who has won three consecutive Formula One championships and won 21 of 23 races this year.

Maybe Noah Lyles, who became the first man since Usain Bolt in 2015 to win the 100 meters, the 200 and participate in a winning 4-by-100 relay team at the World Championships.

Or maybe Mondo Duplantis, who set the pole vault record for the seventh time in his career when he soared 20 feet, 5 ½ inches.

Or Aitana Bonmati, who was the outstanding player every time she played in a tournament in 2022-23, including Spain’s victory in the World Cup.

Or Erling Haaland, the 6-foot-4 Norwegian who joined Manchester City and immediately scored 36 goals, breaking the Premier League record for a first-year player.

All are worthy. But sometimes a person’s impact doesn’t surface until years later.

For that reason, Ed O’Bannon would be a Sportsperson of the Year that would make Sports Illustrated proud, back when pride was within its capabilities.

O’Bannon led UCLA to its last NCAA basketball championship 28 years ago. He noticed that one of the video games was using his Name, Likeness and Image, a phrase that was distilled into one the most significant acronyms in recent sports history.

O’Bannon initiated a suit that, nine years ago, opened the door to NIL money for athletes. The journey from theory to reality was long, but now college quarterbacks make millions, players transfer and play immediately, and conferences crumble as schools play the angles for TV money that neither O’Bannon nor anyone else could imagine.

It might have happened anyway but O’Bannon was the midwife. And even though everyone squirms over what it’s become, there’s no question that college athletes are living in a more real world than ever before.

So O’Bannon earns the urn, if it’s still intact. And here it is in your mailbox. If we could restore the run to the street, and the opening of the door. and the uncertain anticipation of what might be inside, and the mastery of the product itself, we surely would.

I could have listed 30 or so others.

What a walk down memory lane. Deion is a travesty. But he and CU are just the reductio ad absurdum of where D1 sports have been going.