To hell and back: Rex Chapman's self-guided tour

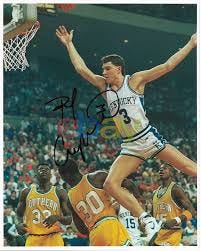

The Kentucky legend and 12-year NBA veteran has written a raw, harrowing memoir.

Had anyone else written Rex Chapman’s story, few publishing houses would have bought it. It relentlessly exposes Chapman’s compulsions, his weaknesses, his consistently poor judgments. At times it’s almost cruel.

Instead, the author is Chapman himself, the former Kentucky hoop prodigy who chased glory and money while addiction and injury were chasing him. The ensuing pileup was spectacular, removing loved ones from his life and stripping every dollar and almost every dollop of self-esteem. He leaves us on the slow climb back to fulfillment, hopeful but mindful that he wakes up each morning to a zero-zero scoreboard. Because of all that, “It’s Hard For Me To Live With Me” is near-imperative reading, for anyone who has ever held a basketball or been in the grasp of anything else.

Chapman is 56 now. He was sort of a high school equivalent of Caitlin Clark when he grew up in Kentucky, an offensive dynamo with unusual levitation, son of a coach who, after watching Rex score 45 on one high school night, asked him, “When are you going to take a f—----- charge?” He was already attention-challenged and prone to irrational risk, including car mishaps and a general contempt for authority, and also had a talent for dodging consequences. That tendency would flourish at the U. of Kentucky, a place he never wanted to attend until he visited and realized he’d be treated like an oil-state potentate. Chapman rarely slept alone during those days, and his teammates joked that his jersey would be retired at Wildcat Lodge, the team’s five-star dorm. He also enjoyed shaking hands with boosters, because his hand would usually emerge with some fresh currency.

But there were two problems. One was the late Eddie Sutton, Kentucky’s coach, whose alcoholism is no secret now but was shielded back then. “We are walking down the hallway,” writes Chapman, who effectively chose to write the entire book in present tense with collaborator Seth Davis, “and see two legs sticking out of the offices. We walk up to the legs and see it is Eddie, completely passed out on the floor.”

Drinking was one of the few problems Chapman never had. But Chapman never warmed to Sutton, and vice versa, and one reason was the general concern over the identity of Chapman’s girlfriend Shawn Higgs, who was Black. This started in Owensboro, Ky., when Chapman was in high school. Bitterly, he notes that Sutton would say the same thing everyone else did: “It’s fine with us, but we’re just concerned about what other people will say.” Some of those other people keyed Chapman’s car with racist messages. Both reactions were equally painful.

In a cinematically-perfect version of this book, Rex and Shawn would have survived all this, including the abortion she had while both were at Kentucky, and become an inspirational couple. Instead the relationship broke. Racism wasn’t the only reason, but it remains a major trigger for Chapman, who still can’t digest the sight of Sen. Mitch McConnell stepping off a plane in front of an aide who had a Confederate flag decal on his briefcase. After all these years he clearly hears the “compliment” from the fan of a rival high school: “You play like a n—----. But when it’s over, you get to be white.”

Sportswriters and other evaluators almost always compared Chapman to white players. Kyle Macy? Chapman couldn’t see it. He thought he was much more like Louisville’s Darrell Griffith, and he was right. Through 12 NBA seasons, Chapman averaged 14.1 points, and in one playoff series for the Suns he averaged 24.2. He also was the runnerup in a Slam Dunk contest. He felt comforted by the NBA and its sense of extended family. When Charlotte took him with the eighth pick in the 1988 draft, he became close to shooting guard Dell Curry, the man whose starting job he was pursuing. In fact he even baby-sat and changed the diapers of his son Stephen.

But the merciless 82-game schedule got Chapman, methodically tore up his feet, dislocated his ankle, broke his thumb. He also suffered from a leaky wallet. He indulged his own gambling addictions, often spending entire days at Off Track Betting parlors, which might be the very definition of degradation. One day his eight year old son Zeke found Rex’s racing tickets in the car, the detritus of a bad day at the track. Zeke proudly added the numbers and announced that Rex had lost $30,000. “I feel like the worst f—----- dad who ever lived,” Chapman writes.

But the worst affliction was appendicitis, because of what happened post-op. A doctor gave Chapman OxyContin for the pain. “Within two days, I am in love,” Chapman says. OxyContin took Chapman into back alleys, into shadowy deals with suppliers, out of his marriage and finally into an Apple Store in Phoenix where he began stealing supplies and selling them just because he needed the cash. He was arrested for that, but eventually dodged a jail sentence, continuing a long history of escape. However, he lost his NBA front-office jobs and began leaning on his friends to get by.

Nine years have passed since Chapman got clean, since he developed a sore throat in the rehab center because it had been so many years since he’d laughed so much. Eventually he developed a considerable social media presence, posting videos of various collisions involving people and animals, and called it “Block or charge?” When someone recognized him and asked if he was “the Twitter guy,” he was delighted.

He is now a podcaster. The book will help get back to his real talent, which is analyzing basketball, either at courtside or in the studio. Maybe there’s an NBA front office that will ask him back. He has repaired his ties with his kids and is in another relationship.

“Sometimes I wish I could take myself in smaller doses,” Chapman writes, “but in the end I guess we’re stuck with each other,” and that explains the purpose of this autobiographical hellride. It’s actually Chapman’s peace treaty, with himself.

Outstanding, Mark. Makes me want to buy Rex's book. Your posts have become "can't miss".

Loved your closing sentence ... hits home ... will be buying the book and probably a couple gift copies. Thanks again, Mark.