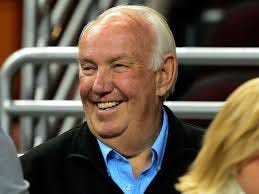

Wherever he hung his clipboard, John Robinson was home

A happy warrior and a formidable coach leaves us, at 89.

John Robinson loved football unconditionally. In a rare and happy coincidence, football loved him back.

He coached and won in college and the pros, and very few coaches in any sport have followed a holy figure like John McKay and not only survived but thrived. When his days of high-profile coaching ended, Robinson was the volunteer defensive coordinator at San Marcos High in San Diego County. “It’s a policy that they have to take somebody from the old folks’ home every couple of weeks,” he explained.

After that he was part of Ed Orgeron’s LSU crew, when Joe Burrow and the Tigers rolled to the 2019 national championship. He served as Orgeron’s sounding board and observational adviser. On Monday he passed away, at 89, thanks to complications from knee surgery that turned into pneumonia. Maybe he sensed there would be another sideline to walk.

The breaks always even out for coaches, they say, but Robinson was generally on the plus side. His wife Beverly was an LSU student in 1979 and always reminded him that the Tigers got shafted in a 17-12 loss to USC. There was also a Rose Bowl in which Charlie White seemed to have scored a crucial touchdown by crossing the 1-yard-line. And there was the Notre Dame game in 1982, the final game for Robinson in his first tour at USC. “Win one for the fat man,” he told the Trojans, and Michael Harper leaped for the winning score. Some Irish fans noted that Harper had reached the end zone without an essential companion, the football. The Notre Dame coach was Gerry Faust, who also died Monday and was also 89.

But fate didn’t always smile. Robinson became the Rams coach in 1983, Eric Dickerson’s rookie year. Dickerson ran for 2,105 yards in a season, still the NFL record. “But we never had the quarterback, and when we got him we didn’t have the running back,” Robinson said. The Rams traded Dickerson after a holdout just as he was supposed to play his first full season with Jim Everett, whom they didn’t sign until late in his rookie year. A work stoppage was the final kibosh on that 1987 season.

Robinson got the Rams to two NFC championship games but ran into superpowers, in the days before the NFL salary cap. The ‘85 Bears dismantled the Rams on a freezing day in Soldier Field, and quarterback Dieter Brock had no chance. “He had played in Canada so I thought he could handle it,” Robinson said, “but then I realized he went to Auburn.”

In 1989 the Rams had morphed into fearsome passers, thanks to the scheming of coordinator Ernie Zampese. In the NFC semifinals, Flipper Anderson took Everett’s game-winning pass through the end zone in Giants Stadium and all the way through the tunnel. But that last step to the Super Bowl was like Everest. The 49ers, who had darkened the Rams’ door throughout Robinson’s tenure, won that NFC title game, 30-3.

The Rams simply weren’t as committed to winning as Robinson needed them to be. But he always had a Pro Bowl-studded offensive line and a running back that didn’t need a warranty. He also had terrific coaches: Zampese, Fritz Shurmur, Norv Turner, Hudson Houck, Dick Coury, Bruce Snyder, Gil Haskell, Artie Gigantino. They trained at an old elementary school, across the street from a Costco in Anaheim, utterly invisible to the thousands who drove by it daily, bereft of creature comforts. But to Robinson it had a marked-up field and some meeting rooms, and that was enough.

Successful coaches create an atmosphere. Robinson’s was generally sunny and mild, like California in the fall. He was the buffer between the team and the Cheap Sheep management, which eventually moved the club to St. Louis for a few dollars more and a new domed stadium. He considered Rams Park a workplace, nothing more or less, and players and coaches were free to be themselves and say whatever they wanted. After games, he would tell the TV reporters, “I’ll take care of you guys in a minute. I’m going to take care of the press first.” The writers liked that, as most human beings would.

If the business ever gnawed at Robinson, he never showed the scars. He recognized the outside world. He had tickets to the L.A. Philharmonic, listened to classical music in the car, and was a fan of haute cuisine. That stuff didn’t interest John Madden, Robinson’s boyhood friend from Daly City, who had left coaching abruptly because of his airborne claustrophobia. Madden, of course, was obsessed with football until the day he died, having revolutionized the role of TV analyst. As kids, the two of them consumed as much football as one could in the pre-Internet days and, although Madden played briefly for the Eagles, they knew they would coach eventually. Robinson was on the Oregon roster and watched most of a Rose Bowl loss to Ohio State on the sideline, as receiver Ron Stover had a big day. Robinson came in for the final play. The clock hit zero and an exhausted Buckeye player embraced him and said, “You played a great game today.” He thought Robinson was Stover.

McKay had been an assistant at Oregon when Robinson played there and before he launched USC into the stratosphere. Robinson was working for McKay when Madden called and made him the playcaller for the Raiders. But that lasted only one year. McKay left to coach the Tampa Bay Buccaneers. Assistant coach Dave Levy was the front-runner for the job, but USC president John Hubbard had always noticed Robinson and liked his teaching approach. Hubbard hired Robinson and the two of them were together, hiding in a L.A. Coliseum office and waiting for the crowd to file out, after Missouri introduced Robinson to head coaching with a 46-25 win. A letter arrived that declared Robinson a “stupid jerk.” The Trojans won the rest of their games, including the Rose Bowl, and Robinson saved the letter. When an envelope arrived with the same handwriting, he opened it to read the apology. “Don’t get cocky, Robinson,” it read. “You’re still a stupid jerk.”

Not for long. In his third and fourth seasons Robinson was 21-1-1 and won Rose Bowls. The ‘78 team had 17 NFL players. The ‘79 team had 18, and ten players drafted, including three first-rounders. Sure, Robinson had a full truckload of talent, but so did Phil Bengtson when he followed Vince Lombardi, and Gene Bartow when he followed John Wooden, and Fred Akers when he followed Darrell Royal. McKay, although quick with the one-liners, was aloof and forbidding. Robinson was accessible and inclusive, but he made sure his standards were met. The testimonials on Monday, from ex-Trojans like Ronnie Lott and Marcus Allen, were unusually emotional. But even Ahmad Rashad, who was at Oregon when Robinson was an assistant, said Robinson jump-started his career.

Robinson stepped away to become an executive vice-president of something-or-another at USC. He had talked himself into thinking he was done with coaching, but when he realized he wasn’t waking up before sunrise anymore, and that Saturday was just another day on the calendar, he thought better of it. The Rams called, and when Robinson’s time came and went there, USC hired him again. As second acts go, it certainly was better than Joe Gibbs’ or Bud Grant’s or Bud Wilkinson’s. The Trojans won the 1995 Rose Bowl over Northwestern, and they pumped out pros like Keyshawn Johnson and Tony Boselli. But inevitably he fell out of step, and USC replaced him gracelessly, with Robinson saying he got the axe from Mike Garrett via answering machine.

UNLV called and, no doubt to its surprise, Robinson answered. The Rebels were 0-11 the year before. To this day they have played in only four bowl games, but Robinson coached in one of them, after an 8-5 season.

Although people in L.A. are generally unaware of this, there is another USC. South Carolina’s coach is Shane Beamer. His team won at Vanderbilt on Saturday, but Beamer was irked over Vanderbilt’s refusal to allow the school’s avian mascot, Sir Big Spur, to attend the game. Vanderbilt bans all live mascots from its stadium, except for its own Jon Meacham.

One of Robinson’s shortcuts to contentment was a refusal to let his own feathers ruffle. Unlike those who say they love the game and actually mean they love the money and the lights, he was devoted to the game and its players. And he never asked for love as part of the transaction. That, of course, is why it returned.

Very nice.

Wonderfully written. What a great coach he will always be. RIP