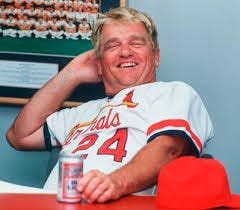

Mighty Whitey, the baseball king of Missouri

Herzog, who left us last week at 92, was always a step ahead.

It was the final game of the 1979 season, a loss to Oakland at home. Whitey Herzog, the Kansas City manager, ran into George Brett on the way out of the clubhouse.

“What are you doing tomorrow?” Herzog asked him. “I thought maybe we could go hunting.”

“Sure,” Brett said.

“OK,” Herzog said. “I gotta be back here at the ballpark at 9 o’clock because I’m gonna get fired. So meet me in the parking lot at 9:15.”

“What?”

“You heard me,” Herzog said.

So Brett pulled in the Kaufman Stadium parking lot at 9:15 and here came Whitey, having packed up his office possessions and put them in a cart.

“What happened?” Brett said.

“I showed up at 9 o’clock and they fired my ass,” Herzog said. “So let’s go hunting.”

Fired? Sure, the Royals had lost the pennant by three games to the Angels. But that was the only year they hadn’t won the American League West since 1975. That was the year Herzog took over for Jack McKeon at midseason and went 41-25 to finish second. The Royals ruled the West the next three years and set club attendance records for four consecutive years, which wasn’t supposed to happen in a small MIdwestern market. Neither were the Royals supposed to thrive in the free-agent landscape. But they did, and they were solid enough to win it again in 1980, the year after Whitey left, and this time they won the A.L. pennant, too.

The reason Herzog knew he would get fired was that he’d complained a little too often about Ewing Kaufman, the owner, and how he didn’t want to spend for stardom. “The Yankees go out and sign Reggie Jackson, Sparky Lyle and Rich Gossage and we sign Jerry Terrell,” Herzog said. That, along with some bullpen mistakes Herzog made in an ALCS loss to the Yankees, was enough.

That was also Whitey. A lot of winning, a lot of laughs, a lot of tumult. When the Royals won one pennant he participated in the champagne ceremony as he wore a T-shirt that read, “I’m a F—---g Genius.”

To be sure he was not confused about what his players meant to him. When he was with the Cardinals and Bruce Sutter left for Atlanta, Herzog said, “I just got 40 games dumber.” But he was sure he knew what a ballplayer was, or wasn’t, and he didn’t mind telling you.

For that and for his splendid record, Herzog made the Hall of Fame in 2010 even though he only won one World Series (1982, with St. Louis). He died on Tuesday, at 92, still an idol in both of his Missouri stops, a guy from small-town Illinois who went a long way being smart, tough and funny.

Herzog actually built his resume with the Mets, where he was the third base coach and then the farm director. Much of the 1969 championship team, and 1973 National League championship, was his creation. He was mortified when the Mets traded Nolan Ryan and Amos Otis (to Kansas City, where he would star for Herzog) and he was livid when the Mets wouldn’t hire him to replace manager Gil Hodges, who died of a heart attack. Indeed, owner M. Donald Grant told Herzog to stay away from him at the funeral, just to douse those rumors.

Herzog never thought he’d ever work for a general manager as sharp as himself. When he got total control in St. Louis, he was as giddy as a shoemaker at an alligator farm. The 1980 winter meetings at the Anatole Hotel in Dallas were basically a Whitey-palooza. He showed up every day to announce a different blockbuster. Fourteen players went out, nine came in, and he basically had Rollie Fingers for a day before he packed Fingers, Pete Vuckovich and Ted Simmons to Milwaukee. He also traded catcher Terry Kennedy to San Diego and later said, “I could be Executive of the Year with three different clubs.”

But the main beneficiary was St. Louis, mainly because Herzog got Ozzie Smith for Garry Templeton, and traded Leon Durham and Ken Reitz for Sutter. Smith and Sutter were both Hall of Famers, and the Cardinals had the best record in the N.L. East in 1981. They went nowhere because the season was split because of a work stoppage, and only the first place teams in each half went to the playoffs. In 1982 they beat the Brewers in the World Series.

Herzog also pilfered Willie McGee, a batting champ, from the Yankees for Bob Sykes, and got Lonnie Smith from the Phillies in a 3-way deal. When Vince Coleman came to the big leagues, the Cardinals had the most fearsome sprint-relay team in baseball history, and then Herzog traded four players to San Francisco for slugger Jack Clark. That team went to Game 7 of the 1985 World Series only because first base umpire Don Denkinger made a faulty safe/out call at the end of Game 6, and the Royals won and then won the next night. Herzog was beside himself, but later he publicly forgave Denkinger and even brought him to speak at Herzog’s educational foundation dinner. In 1987 the Cardinals got to another Game 7 but lost at Minnesota, when Clark was injured.

In the dugout Herzog was a farsighted manipulator of relief pitchers and didn’t mind asking Sutter for six or even nine outs. He also looked at the artificial turf in Busch Stadium and the faraway fences, and turned the place into a dragstrip. In 1985 the Cardinals stole 314 bases and hit 87 home runs. They also had 59 triples.

Herzog could be quite entertaining. “I’m only two players short of winning the whole thing — Babe Ruth and Sandy Koufax,” he would say. Of his decent but not overwhelming playing career, he observed, “Baseball has been very good to me since I quit trying to play it.”

He could also be ornery and belligerent. Most people remember Herzog forcibly pulling Templeton into the dugout after the shortstop failed to give a 90-foot effort, but in an ALCS against the Yankees, Herzog knew that slugger John Mayberry had been overserved the night before and benched him after a popup got away. Then he refused to play Mayberry in the clinching game, and Kansas City lost.

When Ryne Sandberg of the Cubs tied a Saturday afternoon game in Wrigley Field with a grand slam and then won it with another homer, Herzog was asked repeatedly how good the kid could be. “He’s Baby F—---g Ruth,” Herzog groused. “Best ballplayer I ever saw.”

Through it all Herzog was a realist. He would trade sentimental favorites. He would play unconventional lineups. He could sense when something was coming down the pike, like a 9 a.m. call to the ballpark. And he never quit listening to the muse that served him best. “I’d have to say I was the best player development man who ever drew a breath,” Herzog wrote in “White Rat,” his autobiography. One assumes he still felt that way, until his last one.

Whitey was a character. I hated those small-ball Cardinals team, but they were always good.

I remember the great Bob Wright once saying “The thing I love about Whicker is he’ll fly from LA to Philly with a stopover in St. Louis and bang out a Whitey Herzog column while he’s there.”

Wrightie would’ve loved this one.